Nuclear Race To Moon: Will India Switch Sides In The Lunar Race & Join Russia & China To Challenge U.S.?

One of the unintended consequences of the U.S. President Donald Trump virtually dumping India out of favor on the ostensible grounds of divergence in trade issues and the Modi government buying Russian oil is the prospect of America competing against a formidable combination of China, Russia, and India in what is the new race to get a strategic foothold on the Moon.

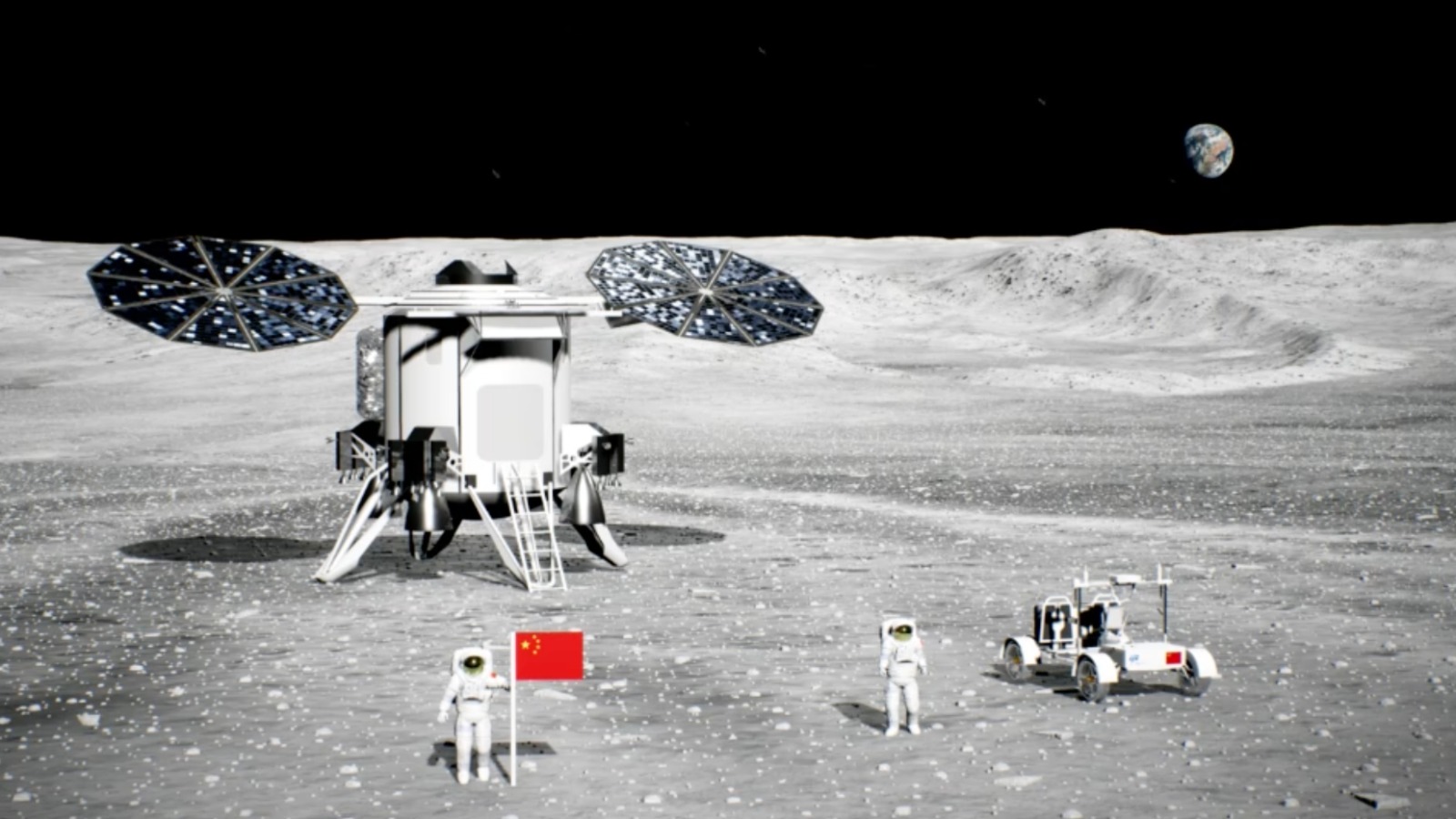

With landing on the Moon becoming old news for these four countries, the race is now to build infrastructure first in the coveted south polar region of the Moon so as to establish a sustained human presence.

And since building any infrastructure needs an assured supply of energy round-the-clock, the race, to begin with, is on being first to deploy a nuclear reactor on the Earth’s closest celestial object, the Moon.

So keen to win this lunar race the Trump Administration is that despite proposing a reduced budget for the NASA by about 24%, from nearly $25 billion to nearly $19 billion and at least 20% of the workforce opting to leave the agency, it now wants that a U.S. reactor must be operational on the Moon by 2030.

It seems that China’s unveiled plans in April this year to build a nuclear power plant on the Moon by 2035 has forced the U.S. to counter the Chinese move by planting its lunar reactor five years earlier.

NASA’s acting Chief Sean Duffy declared early this month: “We’re in a race to the moon, in a race with China to the moon. And to have a base on the moon, we need energy”. Accordingly, he has directed the Agency to launch a 100-kilowatt nuclear reactor to the moon by 2030.

In fact, Duffy went further than simply saying he wants the United States to beat China to the Moon. He said that he wanted the U.S. to claim the “best” part of the Moon for itself.

“There’s a certain part of the moon that everyone knows is the best. We have ice there. We have sunlight there. We want to get there first and claim that for America.”

And that part happens to be the south polar region. Apart from the water availability, this area of the Moon is more convenient for resource extraction.

It is believed that the Moon holds over a million tons of helium-3, largely absent on Earth. Fusion reactors using helium-3 could deliver clean energy with minimal radioactive waste, offering a major edge to early access nations.

The Moon is also believed to contain enormous rare earth elements vital for semiconductors, clean technologies, and defence.

Since at present China is said to be processing 70 percent of the rare earth elements, lunar alternatives could reshape or reinforce global supply chains, so runs the argument.

It may be noted that China’s plan to build a lunar reactor that was unveiled in April is part of its joint effort with Russia to develop the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), a long-term scientific outpost near the lunar south pole.

The ILRS is envisioned as a scalable and autonomous lunar base that will support a wide range of scientific and technological missions. The nuclear reactor is expected to ensure reliable, long-term power generation in the challenging lunar environment, particularly during the two-week-long lunar nights.

Importantly, Russia would like India to join in this joint effort to make it a trilateral project. Alexey Likhachev, CEO of Russia’s atomic energy corporation Rosatom, has said that India has shown interest in this venture.

“The task we are working on is the creation of a lunar nuclear power plant with an energy capacity of up to half a megawatt. Both our Chinese and Indian partners are very interested in collaborating as we lay the groundwork for several international space projects”.

Of course, this information had come through a lecture of Likhachev at Vladivostok last September. India, or for that matter China, has not acknowledged it, though neither has denied it.

India’s reticence could be due to the fact that Russia’s invitation might have been misunderstood by the U.S., which was actively pursuing its romance with India in those pre-Trump days. Besides, India’s ties with China had not been fully defrozen.

But now things are different. India seems to have become one of Trump’s enemy countries, and India-China relations are improving rapidly.

Not only is Modi scheduled to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin at the end of this month during the SCO summit in China, but foreign ministers and national security advisers of India and China have already met. In fact, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has just concluded his trip to New Delhi.

In other words, Sino-Indian relations, strained since their border clash in 2020, are speedily normalising, thanks to Trump.

In any case, it has been widely reported how India is actively seeking out potential opportunities to accelerate its space ambitions.

Its ambitions have got a huge boost with its spacecraft landing successfully on the Moon in August 2023, and thus joining a select space-faring club comprising China, Russia, and the United States – the only nations to have ever reached the only satellite of the Earth.

Be that as it may, a lunar base is said to be the equivalent of the International Space Station (ISS) – somewhere people can live and work for long periods. It can serve as both a proving ground for advanced space technologies and a strategic launch point for future Mars missions.

For this, it has to be a sustainable base that would overcome some of the harshest conditions in the solar system, from extreme temperature swings to two-week-long nights with no sunlight.

And for this, a nuclear reactor is seen as the only practical alternative to solar power, though available, it is not durable. Because of the Moon’s long periods of darkness – 14 days out of each 28-day period – solar panels as a source of power would be operative only 50 per cent of the time because of their dependence on the rays of the sun.

On the contrary, nuclear generators operate independently of sunlight and can provide power continuously. If you want a truly reliable energy source, you need a nuclear reactor.

It may be noted that during Apollo missions (1969), astronauts had used chemical fuel cells, which were fine for very short stays with limited power needs. Even then, for the flight in November 1969 of Apollo 12, astronauts Charles Conrad and Allan Bean, the second pair of men to walk on the surface of the moon, took with them a nuclear generator and set it in position to provide the electricity to operate scientific instruments and subsystems, which were providing continuing information.

In his report at the end of 1969, Dr. Glenn T. Seaborg, Chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission, reported that the generator was successfully withstanding immense temperature variations on the Moon. In that sense, atomic energy is not new on the Moon.

Of course, setting up a reactor on the Moon is a challenging task, involving designing something that can be shipped to the Moon, and then assembled and connected on-site as simply and safely as possible. Then there is the issue of dealing with nuclear waste.

However, there appears to be a global consensus in the scientific community that the engineering and logistical challenges of an atomic plant on the Moon can be successfully met, though the process may take longer than planned.

It is said that while enriched uranium and alloys need to be shipped from Earth, the Moon offers silicon, aluminium, and iron – suitable for structures and shielding. Accordingly, a hybrid model may emerge, with core parts from Earth and outer structures.

But the Trump Administration is pressuring its scientists to expedite their work so that the U.S. becomes the first nation to build lasting infrastructure that will shape the rhythm of lunar activity.

As Duffy said in his directive, if China or Russia were to reach the moon first, either country could “potentially declare a keep-out zone which would significantly inhibit” the U.S. from establishing a presence if it is not there first.

The U.S. rationale seems to be that the country that always succeeds first eventually shapes the norms for expectations, behaviors, and legal interpretations. And it wants to be that first country in terms of lunar presence and influence.

However, it is to be noted that the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, ratified by all major spacefaring nations, including the U.S., China, Russia, and India, governs space activity.

The Outer Space Treaty is very clear that no country can stake territorial claims or assert sovereignty in the Moon or other celestial bodies. These are common to mankind as a whole. The Treaty, therefore, stresses on cooperation rather than competition.

At the same time, the Treaty acknowledges that countries may establish installations such as bases, and with that, gain the power to limit access. While visits by other countries are encouraged as a transparency measure, they must be preceded by prior consultations.

The Treaty’s Article IX requires that States act with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties.”

Effectively, this grants operators a degree of control over who can enter and when. If one country places a nuclear reactor on the moon, others can navigate around it, legally and physically. In effect, it draws a line on the lunar map. If the reactor anchors a larger, long-term facility, it could quietly shape what countries do and how their moves are interpreted legally, on the moon, and beyond.

Incidentally, in 2020, NASA, in coordination with the U.S. Department of State and seven other initial signatory nations, established the Artemis Accords. These Accords provide a common set of principles to enhance the governance of the civil exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon.

The Artemis Accords reinforce the commitment by signatory nations to the Outer Space Treaty, the Registration Convention, the Rescue and Return Agreement, as well as best practices and norms of responsible behavior for civil space exploration and use.

They emphasise peaceful use and transparency – but also introduce “safety zones” that are said to be “not about ownership; they’re about transparency and deconfliction.”

The Accords clearly say that “The Signatory maintaining a safety zone commits, upon request, to provide any Signatory with the basis for the area in accordance with the national rules and regulations applicable to each Signatory.

“The Signatory establishing, maintaining, or ending a safety zone should do so in a manner that protects public and private personnel, equipment, and operations from harmful interference. The Signatories should, as appropriate, make relevant information regarding such safety zones, including the extent and general nature of operations taking place within them, available to the public as soon as practicable and feasible, while taking into account appropriate protections for proprietary and export-controlled information”.

Yet, some experts are worried over the use of the word “due regard” in the Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty and “reasonable” in the clause of the Accords that says, “The Signatories commit to respect reasonable safety zones to avoid harmful interference with operations under these Accords, including by providing prior notification to and coordinating with each other before conducting operations in a safety zone established pursuant to these Accords”.

Because the words “due regard” and “reasonable” can be misused under the plea of preventing interference in one’s “safety zones”. Thus, a nuclear reactor placed on the lunar surface could legitimize what Duffy’s directive calls a “keep-out zone.”

In other words, building infrastructure, powered by the reactor, in an area would cement a country’s ability to access the resources there and potentially exclude others from doing the same, thus potentially violating the spirit of the Outer Space Treaty.

Incidentally, 56 countries, including India (it signed in 2023), are now parties to the Artemis Accords. But neither Russia nor China is a signatory to the Artemis Accords. Both nations have declined to join and have instead chosen to collaborate on their own lunar exploration initiatives, like the ILRS. They talk of promoting UN-based governance.

China’s white paper, which was released in 2022, describes the Moon as “a platform for building a shared future for mankind” and building “the common wealth of all humanity”.

It talks of ILRS and diversified “international exchanges and cooperation in the fields of lunar exploration, space station, planetary exploration, and Beidou navigation, for mutual benefit.”

Significantly, the Chinese paper talked of accelerating the development of a high-quality, sustainable, and beneficial space industry by involving and collaborating with the BRICS members, which include India.

Viewed thus, one can say that before Trump’s tantrums that have jolted Indo-U.S. ties considerably, India, a party to America-promoted Artemis Accords, might have overlooked the Chinese approach towards the Moon, strongly shared by Russia. But now, it may be a different story.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Sicherheit

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Spiele

- Gardening

- Health

- Startseite

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Andere

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture