How can African states protect infant industries while still engaging in global trade? Europeans and American industries and countries now knows what they lost.

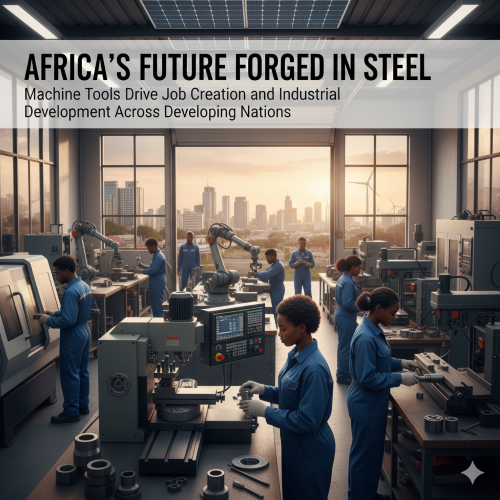

One of the greatest challenges facing African economies is how to nurture infant industries—new or emerging sectors that lack the economies of scale, experience, and technology to compete against established global giants.

Historically, many now-developed countries, from the United States to Germany to South Korea, used protectionist measures to give their domestic industries a chance to grow before fully opening up to global trade.

For Africa, the dilemma is acute: while protection is needed to allow local firms to build capacity, African economies also depend heavily on global trade for revenue, technology, and investment.

The question is: how can African states strike the right balance—shielding infant industries without isolating themselves from international trade networks?

Why Infant Industry Protection is Necessary

-

Unequal competition: New African firms cannot immediately compete with established manufacturers from China, Germany, or the U.S. Without temporary protection, they risk being wiped out before they can mature.

-

Job creation: Protecting local industries allows them to expand employment rather than ceding jobs to imports.

-

Value addition: Africa currently exports raw materials and imports finished goods. Local industries must be shielded long enough to move up the value chain.

-

Technology absorption: Infant industries need time to learn, adapt, and innovate. Premature exposure to global competition often prevents this process.

Without protection, Africa risks remaining permanently locked into the role of a raw material supplier.

Strategies for Protecting Infant Industries

1. Smart Tariff Policies

Tariffs—taxes on imported goods—are the most direct way to protect infant industries. But they must be strategic, temporary, and targeted.

-

Moderate tariffs (10–20%) on finished products that local industries are trying to produce (e.g., machine tools, textiles, agricultural machinery).

-

Zero tariffs on essential raw materials or intermediate goods that African industries need for production.

-

Phased tariff reduction: Tariffs should decline as industries become more competitive to avoid permanent inefficiency.

Example: South Korea used tariffs and import quotas in the 1960s and 1970s to nurture domestic industries before gradually integrating into world markets.

2. Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs)

Sometimes tariffs alone are insufficient. Non-tariff barriers can also protect local firms:

-

Local content requirements: Foreign companies must source a percentage of their materials, labor, or parts from local firms.

-

Quality and safety standards: Ensuring imports meet certain technical standards can give local firms breathing room while promoting higher product quality.

-

Public procurement preferences: Governments can mandate that a significant share of state contracts go to domestic producers.

Impact: NTBs give African industries guaranteed markets while still allowing international engagement.

3. Subsidies and Incentives

Governments can directly support local firms through:

-

Tax holidays for new manufacturers.

-

Subsidized credit or grants for research and development (R&D).

-

Export subsidies to encourage African firms to test global markets.

These reduce costs and make it possible for infant industries to scale up without being crushed by imports.

4. Strategic Use of Regional Trade (AfCFTA)

One of Africa’s greatest assets is the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which creates a market of 1.4 billion people.

-

Infant industries can first build capacity within protected continental markets before competing globally.

-

By harmonizing tariffs across Africa, states can ensure that local firms face reduced competition from foreign imports but still access wider African demand.

-

Regional specialization allows different countries to focus on different industries (e.g., Kenya on renewable energy tools, Nigeria on agricultural machinery, South Africa on automotive).

This mirrors how the European Union nurtured its industries before opening fully to global competition.

5. Time-Bound Protection (“Sunset Clauses”)

Protection should not last indefinitely, or it risks breeding inefficiency and complacency. Infant industry protection works best when paired with performance benchmarks and time limits:

-

Sunset clauses require tariffs or subsidies to expire after 5–10 years unless the industry demonstrates clear competitiveness.

-

Governments must monitor productivity, innovation, and export capacity to ensure protection is fostering genuine growth.

This ensures that protection remains a ladder to development—not a permanent crutch.

How to Balance with Global Trade

Protectionism does not mean isolation. African states must remain engaged in global trade to access technologies, investments, and foreign markets. This can be achieved through:

1. Selective Openness

-

Keep markets open for goods that Africa does not yet produce competitively (e.g., advanced medical devices, aircraft).

-

Protect only those industries identified as strategic for long-term development (e.g., machine tools, renewable energy, agro-processing).

2. Technology Partnerships

-

Use trade and investment deals to secure technology transfer—ensuring foreign firms train local workers, share designs, and establish local R&D centers.

-

Negotiate with both BRICS nations and Western firms to avoid over-dependence on one bloc.

3. Participation in Global Value Chains (GVCs)

Even while protecting infant industries, African states can integrate into GVCs by producing intermediate goods. For example:

-

Supplying parts for global automotive or electronics firms.

-

Providing raw materials for processing under conditions that require local value addition.

This maintains global linkages while nurturing domestic capacity.

4. WTO-Compatible Measures

Infant industry protection must respect World Trade Organization (WTO) rules to avoid trade disputes. Fortunately, WTO provisions allow developing countries more flexibility in applying tariffs, subsidies, and special safeguards. African states should use this legal space strategically.

Risks of Over-Protection

While protection is necessary, it comes with risks:

-

Inefficiency: Firms may become dependent on state support and fail to innovate.

-

High consumer prices: Tariffs often raise prices for domestic consumers, which can be politically unpopular.

-

Retaliation: Trading partners may impose counter-tariffs on African exports.

-

Corruption and rent-seeking: Protectionist policies can be manipulated by elites for personal gain.

Mitigating these risks requires strong governance, transparency, and accountability mechanisms.

Lessons from History

-

United States (19th century): Protected its textile and steel industries until they could compete globally.

-

Germany (late 1800s): Used tariffs and subsidies to build its chemical and engineering industries.

-

Japan and South Korea (20th century): Combined protection with export discipline, requiring firms to prove competitiveness in foreign markets.

-

Africa (past attempts): Many post-independence African states tried protectionism, but weak governance and poor policy design often led to inefficiency.

The lesson is clear: protection works best when time-bound, performance-based, and paired with global engagement.

For African states, protecting infant industries is not a choice but a necessity. Without it, new sectors will never develop the scale, efficiency, and technological know-how to compete globally. Yet isolation is equally dangerous.

The challenge is to strike a dynamic balance:

-

Use tariffs, subsidies, and local content policies to shield emerging industries.

-

Leverage AfCFTA to build scale within Africa before venturing globally.

-

Remain open to trade, technology, and investment in areas where Africa still lacks capacity.

-

Ensure protection is temporary, transparent, and performance-driven.

If done right, infant industry protection will not hinder Africa’s participation in global trade—it will strengthen it by ensuring African firms compete on fairer terms. The goal is not autarky but strategic engagement: trading with the world while building domestic strength.

In essence, African states must remember what the great economist Friedrich List once argued: “Kicking away the ladder” of protection too early condemns nations to dependency. For Africa, the ladder must be climbed—but carefully, with both protection and openness balanced for long-term sustainability.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Seguridad

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Juegos

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture