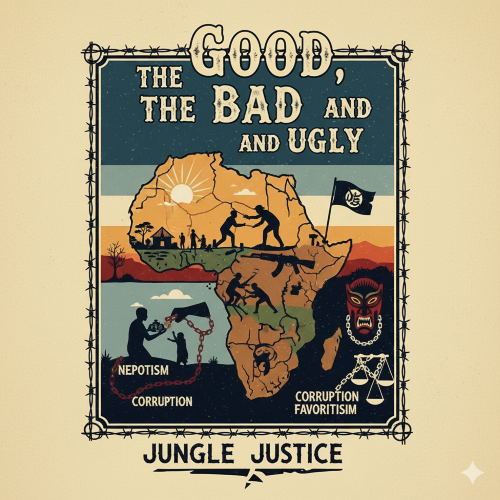

Why do African institutions AU-African Union and ECOWAS remain silent while Northern Nigeria bleeds?

The relative silence of major African institutions, such as the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), regarding the severe and prolonged insecurity in Northern Nigeria is explained by a convergence of political, institutional, and historical constraints.

While both bodies have acknowledged the complexity of the security challenges and provided support to Nigeria's efforts, they have stopped short of the kind of high-profile condemnation or direct intervention that would typically follow mass atrocities in a smaller or less strategically important member state.

1. Sovereignty and the Principle of Non-Interference

The single most significant constraint on African institutions is the fundamental principle of national sovereignty, which remains sacrosanct among member states.

-

The AU Constitutive Act: While the AU transitioned from the Organization of African Unity's (OAU) principle of "non-interference" to "non-indifference," the commitment to sovereignty still holds powerful sway. African leaders are fiercely protective of their right to manage internal affairs without external oversight, fearing that intervention in one country could set a precedent for intervention in their own.

-

Nigeria's Role as a Regional Hegemon: Nigeria is not a small, weak state; it is the most populous country in Africa and historically the anchor of regional stability in West Africa. It is the largest contributor of troops and finances to ECOWAS and AU peacekeeping missions across the continent (such as ECOMOG in Liberia and Sierra Leone). Challenging Nigeria's sovereignty through a high-profile censure or threat of intervention is politically fraught and institutionally difficult, as it risks alienating the region's most powerful partner.

2. Institutional and Financial Limitations

African regional bodies often lack the necessary institutional teeth and independent funding to manage crises in a major power like Nigeria.

-

Lack of Autonomy: The AU and ECOWAS remain largely controlled by their member states, especially the regional hegemons. They lack the institutional autonomy and political consensus to act decisively against a powerful member that rejects their involvement.

-

Capacity and Funding Deficits: While both the AU and ECOWAS have peace and security architectures (APSA and the ECOWAS Standby Force), their operational capacity is limited and often reliant on external funding (e.g., from the EU or UN). Mobilizing a large-scale, sustained peacekeeping or stabilization force within Nigeria, which has Africa's largest military, is logistically and financially impractical for the AU/ECOWAS.

3. Nigeria's Political Strategy of Redefinition

The Nigerian government has actively engaged in a political strategy to define the conflict in a way that minimizes the need for external, high-level intervention.

-

Reframing the Crisis: The government consistently minimizes the scale of the violence by framing it as a matter of "banditry," "local criminality," or "communal clashes," rather than a systematic campaign of terror or mass atrocities. This narrative directly contradicts the criteria often used to trigger robust international action.

-

Rejecting Religious Narratives: The AU has publicly aligned with the Nigerian government's stance, rejecting narratives, particularly from the US, that oversimplify the crisis as a targeted persecution or genocide against Christians. AU officials argue that the violence is multifaceted, rooted in political and economic instability, and affects citizens of all faiths. They caution that weaponizing religion hinders effective solutions.

4. Competing Priorities and Crisis Fatigue

African institutions face a constant barrage of crises across the continent, forcing them to triage their attention and resources.

-

Contiguous Instability: The AU and ECOWAS are simultaneously dealing with:

-

The Sahel Coup Belt (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger) and the breakdown of democracy.

-

The ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Sudan.

-

The expansion of jihadist groups toward coastal West African states (Togo, Benin). The sheer number of concurrent crises forces a generalized response, preventing a focused, sustained effort on Nigeria's internal insecurity.

-

-

Risk of Contagion: Any forceful intervention or public condemnation against Nigeria could have the unintended consequence of destabilizing the entire subregion, especially given the deep economic and security ties between Nigeria and its neighbors. African institutions prioritize actions that prevent further regional contagion.

In conclusion, the perceived silence of African institutions while Northern Nigeria bleeds is a consequence of a politically rational calculation. Intervening decisively against a major member state like Nigeria risks violating the cardinal principle of sovereignty, overstretching limited institutional capacity, and potentially destabilizing the entire region—a risk African leaders are highly unwilling to take.

They prioritize providing quiet, technical support while endorsing Nigeria's official narrative, thereby preserving regional political cohesion and stability over immediate, high-profile accountability for atrocities.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Sicherheit

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Spiele

- Gardening

- Health

- Startseite

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Andere

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture