Are America’s Checks and Balances Still Working—When It Comes to Financial Crimes and Elite Accountability?

In theory, the United States has one of the most sophisticated systems on earth for preventing financial corruption: an independent Congress, a powerful judiciary, a free press, and multiple oversight agencies.

On paper, this should make large-scale financial wrongdoing almost impossible to hide. In reality, however, the system works very differently depending on who commits the crime.

When ordinary citizens or small-scale actors break financial laws—fraud, tax evasion, theft, misuse of public funds—the consequences are swift and severe. When wealthy elites, corporate giants, political insiders, or senior government officials engage in similar behavior, accountability becomes slow, fragmented, or nonexistent.

This raises the fundamental question: Are America’s checks and balances capable of restraining financial wrongdoing at the highest levels of power?

The answer is increasingly troubling. The institutions designed to prevent abuse still exist, but when dealing with financial crimes by the powerful, they often function unevenly, inconsistently, or symbolically rather than substantively. The erosion is not absolute, but it is real—and growing.

1. Congress: More Prone to Protecting Elites Than Exposing Them

Congress holds enormous theoretical authority over financial accountability:

-

It regulates financial markets

-

It oversees federal agencies

-

It can investigate corporate and political corruption

-

It controls public spending

-

It can refer criminal cases

And yet, when the wrongdoing involves politically connected elites, Congress often fails as a check—and sometimes becomes part of the problem.

1.1 Oversight Has Become a Political Weapon, Not a Search for Truth

Congressional oversight committees once conducted serious investigations into financial crimes:

-

insider trading

-

banking scandals

-

misuse of public money

-

lobbying abuses

-

financial misconduct by officials

Today, however, congressional oversight is often:

-

selective

-

partisan

-

theatrical

-

driven by media optics

If the alleged wrongdoer belongs to the same political party as the majority in Congress, oversight evaporates. If they belong to the opposing party, oversight becomes aggressive—but often driven more by political gain than justice.

1.2 Lobbying and Corporate Influence Complicate Accountability

America has normalized something many other political systems consider dangerous:

-

corporate funding of political campaigns

-

direct access between corporations and lawmakers

-

industry-written legislation

-

lobbying networks with near-unlimited financial resources

This creates a structural conflict of interest. When lawmakers depend on the very corporations and financial elites they are supposed to regulate, genuine oversight becomes unlikely.

1.3 Congress Often Shields Elites From Financial Scrutiny

Examples of elite protection include:

-

weakened insider trading laws

-

limited transparency requirements

-

slow action on corporate tax loopholes

-

refusal to regulate political fundraising

-

partisan obstruction during major financial investigations

In many cases, Congress does not prevent financial wrongdoing—it legalizes or normalizes it.

Verdict: Congress still functions, but when it comes to elite financial crimes, it operates more as a shield than a check.

2. The Courts: Capable of Enforcement, But Selective and Often Slow

The judiciary remains the strongest institutional check. Courts do convict white-collar criminals. They do prosecute insider trading, corporate embezzlement, Ponzi schemes, and money laundering.

But elite financial crime operates differently.

2.1 The More Powerful the Defendant, the Slower the Wheels of Justice

Major financial crimes involving elites often take years before reaching court:

-

endless motions

-

expensive legal defense

-

political pressure

-

jurisdictional complexity

-

strategic delays

By the time a case concludes, public attention has moved on, and political consequences are minimal.

2.2 Prosecutors Are Less Willing to Target the Most Powerful

There is a well-documented pattern in American law enforcement:

-

Prosecute mid-level executives, leave the top untouched.

-

Pursue low-level political staff, avoid indicting senior officials.

-

Focus on individual traders, not the bankers who designed the system.

In the 2008 financial crisis—one of the largest examples of financial wrongdoing in modern history—not a single top banking executive went to prison.

2.3 Money Shapes Outcomes

Wealthy defendants can:

-

hire elite defense attorneys

-

negotiate favorable settlements

-

pay multi-million dollar fines instead of facing trial

-

use influence networks to soften regulatory responses

Meanwhile, small violators of financial law face:

-

quick indictment

-

harsh sentencing

-

compulsory repayment

-

little room for negotiation

This is not equal justice—it is stratified justice.

2.4 Courts Are Still Independent—but Influence Is Real

Judges may be independent, but the system around them is not immune to:

-

political appointments

-

ideological influence

-

corporate pressure

-

prosecutorial discretion

-

resource imbalance

The courts still work—but often too slowly, too unevenly, or too softly for elite financial crimes.

3. The Media: Still a Watchdog, But Frequently Neutralized

Investigative journalism remains essential for exposing corruption. Major outlets still break stories involving:

-

offshore accounts

-

corporate fraud

-

tax evasion networks

-

political corruption schemes

But journalism’s restraining power has declined sharply.

3.1 Media Fragmentation Undermines Accountability

In the past:

-

A major exposé could unite public outrage.

-

There was a shared national information ecosystem.

Today:

-

Different media ecosystems produce opposite realities.

-

Audiences filter news through ideological preferences.

-

Corruption revelations are reframed as partisan attacks.

This allows political and financial elites to escape consequences simply by shifting the narrative.

3.2 Corporations Own Major Media Outlets

When media outlets depend on:

-

advertising revenue from corporations

-

political access

-

corporate parent companies

-

billionaire owners

the incentive to aggressively pursue stories involving those same elites decreases.

3.3 Outrage Fatigue Weakens the Impact

With endless scandals in politics, banking, and corporate America, the public becomes desensitized. Exposés that would have triggered national outrage decades ago now fade within days.

Verdict: The media still reveals wrongdoing, but it no longer guarantees accountability.

4. So Do Checks and Balances Still Restrain Financial Crimes by the Powerful?

The institutions exist. They operate. They occasionally succeed.

But:

-

Congress is too partisan and too entangled with elite interests.

-

The courts are too slow and too selective.

-

The media is too fragmented and too dependent on elite structures.

As a result, elite financial wrongdoing often survives exposure and escapes meaningful punishment.

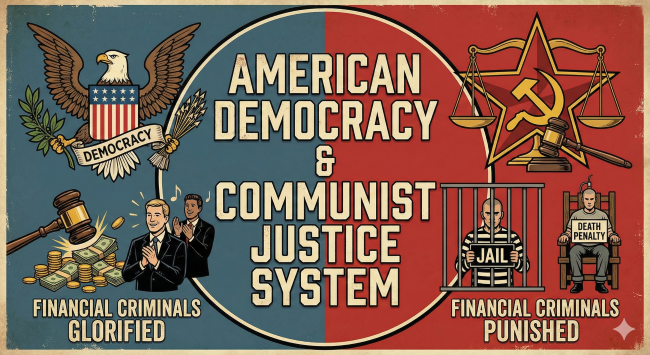

5. The Consequence: Two Systems of Justice

Today’s America increasingly resembles a dual system:

For the wealthy and politically connected:

-

delayed investigations

-

negotiated settlements

-

political protection

-

media polarization

-

judicial leniency

For ordinary citizens:

-

swift prosecution

-

harsh punishment

-

limited access to legal defense

-

public shaming

-

few opportunities for negotiation

This divergence is a sign that checks and balances function strongly downward but weakly upward—a reversal of the constitutional design.

The System Still Exists, But It No Longer Works Equally for All

The traditional checks and balances of the United States were designed to prevent exactly this scenario: a concentration of power and wealth capable of bending institutions in its favor.

But today:

-

Congress is conflicted.

-

Courts are uneven.

-

Media is fragmented.

-

Oversight agencies are politicized.

-

Public trust is eroding.

These institutions still have the framework of accountability—but not the full function of it, especially when dealing with financial crimes committed by elites.

The system is not fully broken, but it is no longer fulfilling the role it was built for. Without major reforms in transparency, campaign finance, regulatory independence, and judicial efficiency, the U.S. risks normalizing a system where accountability flows downward, while protection flows upward.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Security

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Games

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture