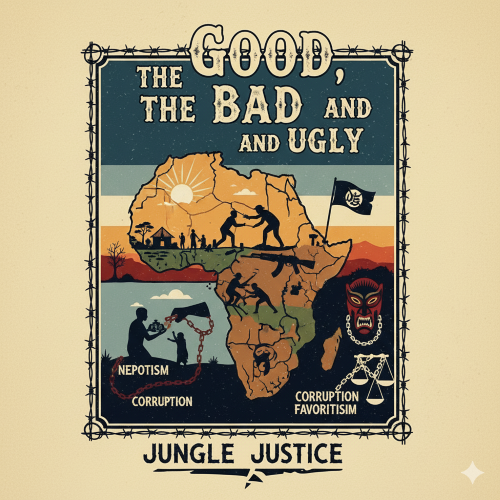

Why are African states quick to condemn foreign wars, yet unwilling to confront African leaders responsible for suffering at home?

The apparent contradiction between African states quickly condemning foreign wars (like the war in Ukraine) while remaining frustratingly unwilling to confront African leaders responsible for immense suffering at home (like in Sudan) is driven by a deep-seated conflict between foundational diplomatic principles, structural limitations, and the immediate self-interest of ruling elites.

This dual standard, or "selective indignation," is rooted in the political DNA of post-colonial Africa, where the norm of state sovereignty often trumps the imperative of protecting citizens.

1. The Clash of Principles: Sovereignty vs. Protection

The African Union (AU) operates under a foundational tension that dictates its response priorities:

-

The OAU Legacy: Non-Interference

The predecessor to the AU, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU, 1963-2002), was founded on the strict, almost sacred, principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of member states. This principle was essential for the newly independent states to prevent external (colonial) powers from meddling and to guarantee their hard-won sovereignty—even if it meant tolerating the domestic abuses of fellow African leaders.

-

The AU Paradigm Shift: Non-Indifference

The AU attempted to shift this paradigm with its Constitutive Act (2000), adopting the doctrine of "Non-Indifference." This allows the AU the right to intervene in a member state—pursuant to a decision by the Assembly—in cases of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity (Article 4(h)). This was a direct response to the OAU's failure to stop the Rwandan genocide and other mass atrocities.

The Reality: While the non-indifference principle exists on paper, the practical political will and legal interpretation of non-interference by the ruling heads of state often prevail. The AU can easily condemn a foreign war (like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) because it involves a non-African state and does not set a precedent for intervention in their own countries. Confronting an African leader, however, threatens to establish a norm that could one day be used against them if they face domestic dissent or cling to power unconstitutionally.

2. Structural and Financial Impotence

Even where the political will exists, the AU is structurally ill-equipped to challenge an armed head of state.

-

Lack of Enforcement Capacity

Confronting a sitting leader or a major warlord (like those in Sudan) requires a credible threat of force, typically a Peace Enforcement Mission. The AU's conceptual African Standby Force (ASF) is still not fully funded, trained, or logistically ready to deploy rapidly and decisively against a high-intensity, urbanized conflict. Past missions (like AMIS in Darfur) have been notoriously under-resourced and forced to transition into hybrid UN operations due to financial strain.

-

Financial Dependency

The AU is heavily dependent on external donors (the EU, UN, US) for funding its peacekeeping and security operations. This dependency means that the speed and scope of African action are often dictated by the political agendas and approval timelines of non-African partners, robbing the AU of the autonomy needed for swift, independent intervention.

-

Selective Application of Rules

The AU often exhibits a double standard in applying its own rules. It is quick to suspend and condemn leaders who seize power through military coups (as seen recently in West Africa) because these are viewed as a direct assault on the constitutional order that all African presidents rely on. However, it is far less likely to sanction leaders who commit "constitutional coups" (like removing term limits, rigging elections, or suppressing civil society) because many sitting heads of state are themselves guilty of similar political transgressions. Condemning these "institutional coups" would be a case of powerful leaders sanctioning their own behavior.

3. The Self-Preservation of African Elites

The most powerful factor is the immediate self-interest and solidarity among ruling elites—often referred to as the "Big Men" syndrome.

-

Fear of Precedent

African leaders share a collective fear that sanctioning a sitting president for human rights abuses or corruption might establish a dangerous precedent. If today they vote to allow intervention in Sudan based on atrocities, tomorrow they might face a similar vote regarding their own country. The internal consensus is, therefore, to defend the principle of sovereignty and non-interference to safeguard their own long-term grip on power.

-

Avoiding the Conflict Spillover

African states that share borders with conflict zones are often reluctant to take a confrontational stance because they fear retaliation from the armed faction or an unmanageable spillover of refugees and armed groups across their already fragile borders. For instance, Egypt and Chad have distinct, pragmatic security interests in Sudan that discourage them from taking a strong, unified line against the SAF or RSF.

-

Strategic Autonomy in Foreign Policy

Condemning a major global power like Russia for a war in Europe is seen as an assertion of African agency and non-alignment. It allows African leaders to critique perceived Western double standards (e.g., in the Middle East) and to define their own foreign policy priorities without direct military risk. This move is popular domestically and provides diplomatic leverage globally, all while requiring no military deployment or financial commitment from the AU.

In summary, the African Union's reluctance to confront African warlords is less about silence and more about institutional paralysis rooted in a fear of undermining the sovereignty principle that protects every incumbent leader. The loud condemnation of foreign wars is a safe diplomatic maneuver that enhances African credibility without costing African blood or treasure, whereas confronting a domestic strongman risks both personal political capital and continental stability.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Security

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Games

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture