Does America Need a New Anti-Corruption Framework to Restore Trust in Its Institutions?

The question of corruption in American public life is no longer a fringe conversation—it is a mainstream concern shared across ideological lines.

Polls consistently show that a majority of Americans believe the political system is rigged to favor the wealthy and well-connected.

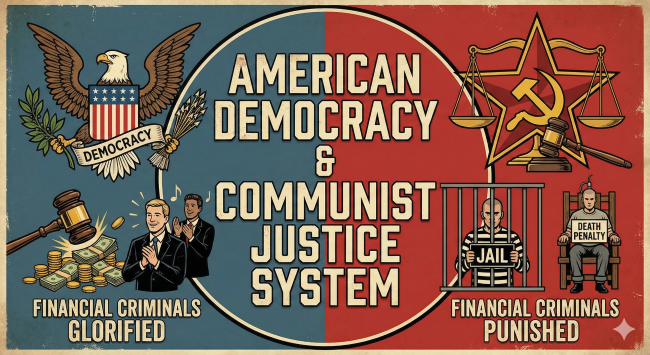

At the center of this belief lies the perception that elite financial crimes go unpunished, political insiders shield one another, and accountability is selectively enforced.

The resulting erosion of trust has left many wondering whether the United States requires not just reforms, but an entirely new anti-corruption framework capable of restoring legitimacy to its institutions.

This question has become urgent because the traditional mechanisms of accountability—Congressional oversight, independent courts, a free press, regulatory agencies—are proving increasingly incapable of disciplining powerful actors. Corruption in the U.S. today is rarely the crude, cash-in-envelope bribery of old. Instead, it is sophisticated, legalized, and integrated into political and economic life, operating through lobbying, campaign finance, revolving doors, selective prosecution, deferred penalties, and informal influence networks that bridge both major political parties.

Against this backdrop, the central issue becomes clear: can trust be restored without building a new anti-corruption system from the ground up?

I. The Crisis of Trust—and Why It Matters

A functioning democracy rests on the belief that institutions act in the public’s interest. When citizens begin to assume that laws are selectively applied, justice becomes transactional, and the wealthy operate by a different set of rules, the legitimacy of the entire system begins to collapse.

Today, that collapse is visible in several ways:

-

Voters believe financial elites evade consequences through political protection

-

High-profile corruption cases are routinely settled without trial

-

Corporate penalties are paid by shareholders, not decision-makers

-

Government agencies often lack independence from political pressure

-

Whistleblowers face retaliation rather than protection

-

Media narratives can be weaponized by partisan outlets to protect political allies

This environment breeds cynicism, polarization, and apathy. It also feeds populist movements—both left-wing and right-wing—that accuse the “system” of being fundamentally corrupt.

If institutions cannot demonstrate that wrongdoing results in tangible consequences, no amount of public messaging, political speeches, or appeals to unity will restore trust.

II. Why the Existing Framework Is No Longer Effective

The U.S. technically has numerous anti-corruption structures, including:

-

Inspectors general

-

Congressional ethics committees

-

The Office of Government Ethics

-

Agency regulatory units

-

Federal prosecutors

-

Anti-bribery statutes

-

Campaign finance disclosures

However, these mechanisms were designed for an era when corruption was:

-

Simpler

-

Less globalized

-

Less technologically sophisticated

-

Less intertwined with legal political activity

Today’s landscape is radically different.

1. Campaign finance has made corruption legal

The rise of Super PACs, dark money networks, and unlimited independent spending has created a system where influence does not need to be hidden; it needs only to be disclosed. Donors do not bribe politicians—they “fund” them. Corporations do not buy protection—they “support candidates who share their vision.” The line between corruption and participation has essentially disappeared.

2. The revolving door creates institutional bias

Former lobbyists run regulatory agencies. Former regulators join the companies they once supervised. This revolving door does not require explicit corruption; shared incentives and networks ensure regulatory softness. Over time, agencies internalize industry priorities.

3. Elite financial crimes are treated differently

Large-scale corporate misconduct is often resolved through:

-

Deferred prosecution agreements

-

No-admission settlements

-

Negotiated fines

-

Immunity for executives

This soft approach signals that the wealthy are shielded from the consequences ordinary citizens face for far lesser crimes.

4. Partisan media shields political allies

Media fragmentation means that even when wrongdoing is exposed, half the country never hears about it—or is told it is “fake news.” Corrupt actors hide behind partisan loyalty, knowing supporters will defend them regardless of evidence.

5. Congress has no incentive to police its own donors

Political leaders benefit directly from the same money systems that feed corruption. The incentive to reform is structurally absent.

Simply put: the existing framework cannot confront corruption that is systemic, legally protected, and reinforced by economic concentration.

III. What a New Anti-Corruption Framework Must Include

Restoring trust requires more than patchwork reforms. It demands a structural overhaul—a new framework built to confront 21st-century corruption. Key components include:

1. An Independent National Anti-Corruption Commission

Many democracies—from Australia to Singapore—have specialized anti-corruption commissions with investigative and prosecutorial authority. The U.S. does not.

Such a commission must be:

-

Independent from political branches

-

Shielded from donor influence

-

Empowered to investigate financial crimes, political corruption, and regulatory capture

-

Capable of prosecuting both private and public elites

No anti-corruption agency can function if appointments are controlled by political donors or party leaders.

2. Criminal liability for executives—not just corporations

Fines paid by corporations do not deter misconduct. They are budgeted as operational risks. Personal criminal accountability must be strengthened, particularly for:

-

Fraud

-

Embezzlement

-

Money laundering

-

Market manipulation

-

Abuse of public office

No more settlements that allow executives to walk free.

3. Transparency for political funding

A new framework should mandate:

-

Full disclosure of all political donations

-

Limits on Super PAC coordination

-

Transparency for dark-money groups

-

Public auditing of campaign finances

Transparency is meaningless if loopholes dwarf enforcement capacity.

4. Protection—not punishment—for whistleblowers

Whistleblowers are the backbone of anti-corruption efforts, yet in America:

-

They are often fired

-

Their careers are destroyed

-

Agencies discredit them

-

Lawsuits drag on for years

The new framework must ensure:

-

Legal immunity

-

Financial compensation

-

Anonymous reporting systems

-

Federal protections enforceable across agencies

5. Strengthened inspector general independence

Inspectors general must be protected from removal, political pressure, and budget manipulation. Their reports should be public by default.

6. Judicial reforms to handle complex financial crimes

Financial crimes require specialized courts or judges trained in:

-

Forensic accounting

-

Corporate structures

-

International transactions

Without expertise, cases collapse under their own complexity.

IV. The Cultural Shift: Why Reform Must Go Beyond Law

Even the strongest legal framework will fail unless the political culture changes. At present:

-

Politicians treat corruption allegations as partisan attacks

-

Voters defend “their” corrupt officials

-

Parties shield donors who bankroll campaigns

-

Media narratives protect elites aligned with their ideological side

An anti-corruption framework must therefore be paired with:

-

Civic education

-

Media literacy

-

Public transparency

-

A cultural revival of ethical leadership

Without a cultural shift, new laws will simply be absorbed into the existing system.

V. Yes, America Needs a New Anti-Corruption Framework—Or Trust Will Continue to Crumble

The United States is not in danger of collapsing into dictatorship. Its problem is more subtle: a quiet slide into a system where elites enjoy structural immunity—where laws function differently depending on one’s wealth, connections, and political usefulness.

If trust is to be restored, the country needs more than reforms. It needs:

-

New institutions

-

New enforcement mechanisms

-

New protections

-

A new political ethic

And above all, a commitment to the principle that no one—no donor, no executive, no politician, no insider—is above the law.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Security

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Games

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture