Corruption in Africa is often perceived as a problem imposed by elites on the population, a one-way exploitation of citizens by those in power. Yet the reality is more complex: ordinary citizens frequently occupy a dual role in perpetuating the system.

They are simultaneously victims of corruption — suffering the consequences of misallocated resources, weak institutions, and systemic injustice — and participants, whether through complicity, survival strategies, or everyday transactions that sustain corrupt practices.

This duality explains why corruption is so resilient and difficult to eradicate, despite widespread awareness of its harms.

1. Citizens as Victims: The Direct Costs of Corruption

The first and most visible dimension of citizens’ involvement in corruption is victimhood. Corruption by political elites and institutions directly harms ordinary people in multiple ways:

-

Economic deprivation: Public resources intended for development are siphoned into private accounts. Hospitals lack equipment, schools are underfunded, roads remain incomplete, and social services fail. Citizens pay taxes and fees but receive substandard services in return.

-

Limited access to essential services: Corruption in healthcare, education, and public utilities often translates into long lines, higher out-of-pocket expenses, or exclusion from services altogether. For example, families may be forced to pay bribes to secure medical treatment or school admission.

-

Inequality and marginalization: Corruption disproportionately harms vulnerable populations. Rural communities, low-income families, and minority groups are often excluded from government programs or development projects, while elites and connected individuals monopolize benefits.

-

Erosion of trust in institutions: Persistent corruption fosters cynicism. Citizens lose faith in government, law enforcement, and the judiciary, perceiving them as tools for elite enrichment rather than instruments of justice and public welfare.

In these ways, ordinary people are clearly victims: they bear the financial, social, and emotional costs of corruption while having limited capacity to influence change.

2. Citizens as Participants: Survival Strategies and Complicity

At the same time, citizens often play a role in sustaining corruption, sometimes out of necessity, sometimes out of complicity. Survival in a corrupt environment frequently requires navigating the very systems that exploit them:

-

Bribery as a means of survival: When public services are underfunded or poorly managed, citizens may pay bribes to access healthcare, secure school admission, obtain official documents, or receive basic utilities. While these actions are technically illegal, they are often seen as the only way to secure essential services.

-

Informal payments and patronage networks: Many African economies operate in part through informal networks of favors and influence. Citizens may participate by engaging in nepotism, favoritism, or local-level exchanges of resources to secure services or opportunities.

-

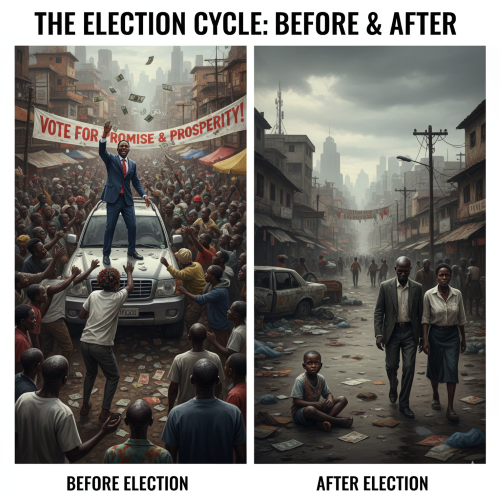

Political compliance for benefits: During elections, citizens often participate in vote-buying schemes, accepting cash, goods, or services from candidates. While they are victims of manipulation, they also reinforce a system where political support is transactional rather than merit-based.

-

Small-scale corruption: In some cases, ordinary citizens act as intermediaries for corrupt elites, such as collecting fees for bribes or facilitating access to public resources. Participation may be motivated by financial necessity rather than ideology, but it perpetuates systemic corruption.

In these ways, citizens are complicit in the very system that oppresses them, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

3. Cultural and Social Pressures

Participation in corruption is not always voluntary; it is often reinforced by cultural, social, and economic pressures:

-

Normalization of corruption: When bribery, favoritism, or nepotism becomes routine, citizens view such behavior as standard practice rather than moral failure. Paying a bribe to secure a permit or service is seen as “just how things work.”

-

Peer pressure and social networks: Citizens may engage in corrupt practices to conform with community norms, avoid ostracism, or gain acceptance. For instance, paying a bribe may be necessary to maintain employment or secure education for children.

-

Expectation of reciprocity: Patronage networks create social obligations. Accepting benefits from political elites may require returning favors or mobilizing support during elections, further entrenching the system.

These pressures blur the line between victim and participant, as citizens often act under coercion, social expectation, or necessity.

4. The Cycle of Dependency and Corruption

The dual role of citizens perpetuates a cycle of corruption that is difficult to break:

-

Short-term gains reinforce compliance: Receiving immediate benefits, such as cash, goods, or access to services, reinforces the expectation that corruption is a normal means of survival.

-

Weak enforcement: As citizens engage in bribery or collusion, the legal and institutional systems fail to function effectively, further embedding corrupt practices.

-

Political manipulation: Politicians exploit citizens’ dependency, providing incentives for loyalty while ensuring that the electorate remains vulnerable to future manipulation.

-

Normalization across generations: Children and young adults observe and learn these practices as acceptable, perpetuating corruption culturally and socially.

This cycle ensures that corruption persists across multiple levels of society, from elites to ordinary citizens, and across generations.

5. Economic and Social Consequences

The dual role of citizens has tangible consequences for society:

-

Stunted development: Misallocation of resources and systemic inefficiency reduce investments in healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social welfare. Citizens suffer reduced opportunities and lower quality of life.

-

Inequality: Wealth and power become concentrated among elites and those with access to patronage networks, while the majority remain marginalized.

-

Erosion of democratic values: Participation in vote-buying or political patronage weakens accountability and undermines electoral integrity. Citizens become conditioned to accept transactional politics rather than demand transparency and performance.

-

Cultural entrenchment of corruption: Corruption is seen as unavoidable, reducing public pressure for reform and discouraging whistleblowing or civic activism.

In essence, citizens’ dual role reinforces structural corruption, limiting the capacity for social and political change.

6. Breaking the Cycle: Empowering Citizens

Addressing the dual role of citizens requires multifaceted strategies that reduce victimization and limit participation in corrupt practices:

-

Civic education: Citizens must understand the long-term costs of corruption and the importance of integrity, both for personal welfare and societal progress.

-

Economic empowerment: Reducing poverty and vulnerability minimizes reliance on bribery or patronage for survival.

-

Strengthening institutions: Transparent, accountable public services reduce the need for citizens to participate in corrupt transactions to access basic needs.

-

Legal enforcement and protection: Whistleblower protections, independent judiciary, and strong anti-corruption agencies can empower citizens to resist and report corruption safely.

-

Promoting social norms of integrity: Community leaders, media, and civil society can shift cultural attitudes, rewarding ethical behavior and discouraging complicity.

By creating an environment where citizens are neither coerced nor compelled to participate, societies can reduce the cycle of corruption and victimization.

Ordinary citizens in Africa occupy a complex position within the corrupt system: they are victims of elite mismanagement, resource diversion, and systemic injustice, yet they also participate in corruption, often as a survival strategy or due to social and economic pressures. This duality sustains the very system that oppresses them, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that is difficult to disrupt.

Breaking this cycle requires structural reform, economic empowerment, civic education, and cultural change. Citizens must be supported in their dual role — protected from exploitation while discouraged from complicity. Only then can corruption be meaningfully reduced, accountability restored, and democratic integrity strengthened, creating a society in which citizens are neither victims nor unwilling participants, but empowered actors shaping their own future.