How has religion been used as a political tool to control and divide African societies rather than unite them?

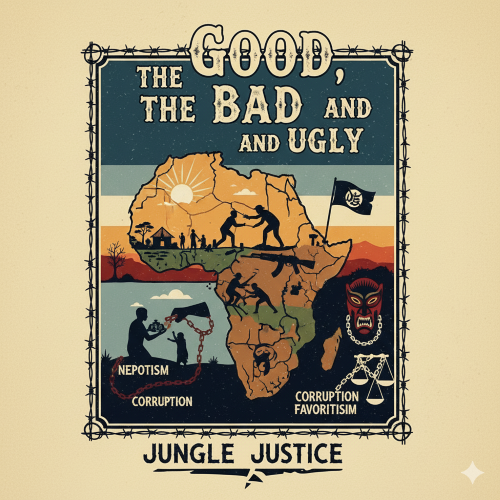

While religion has historically served as a powerful force for social cohesion, resistance, and unity in many African societies, its complex and multifaceted nature has also made it a potent political tool for control, division, and the manipulation of power.

The usage of religion in this manner is not singular, but a layered phenomenon that intersects with colonialism, post-colonial politics, ethnic identities, and socioeconomic inequalities.

1. The Colonial Legacy: Christianization as a Tool of Control

The most prominent historical use of religion as a political and divisive tool in Africa stems from the era of European colonialism. Christian missionaries often arrived hand-in-hand with colonial administrators and traders, and the process of Christianization was frequently instrumentalized to dismantle existing social structures and facilitate control.

A. Undermining Indigenous Systems

Colonial powers, and the missionary societies that often acted as their cultural vanguard, typically viewed Indigenous African Religions (IARs) as "primitive," "superstitious," or "pagan." This created a powerful moral and cultural justification for conquest. By promoting Christianity, colonizers sought to:

-

Delegitimize Traditional Authority: Many IARs were intrinsically linked to the authority of chiefs, elders, and spiritual leaders. Conversion to Christianity often meant rejecting the spiritual basis of their power, effectively undermining the traditional governance structures that could have organized resistance. For example, the rejection of ancestral veneration severed a crucial link between the living and the past, fragmenting the spiritual foundation of community solidarity.

-

Establish a Hierarchy of Civilization: Christianity was presented as a marker of "civilization" and progress. African converts were often granted preferential access to education, civil service jobs, and resources, creating a new, religiously-defined elite class loyal to the colonial administration. This immediately created a schism between the Christianized and the non-Christianized segments of the population.

B. Education and Cultural Homogenization

Mission schools were the primary vehicles for colonial education. While they undeniably brought literacy and modern skills, their curriculum was meticulously crafted to foster religious and cultural assimilation.

-

Linguistic and Cultural Suppression: Students were often forbidden to speak their native languages or practice cultural rites. The new, standardized Christian morality and worldview supplanted diverse local customs, leading to a sense of cultural inferiority among the colonized and furthering the division between those who embraced the new culture and those who resisted it.

-

Creating a Subordinate Bureaucracy: The products of these schools—clerks, interpreters, and lower-level administrators—were essential to the colonial machinery. Their religious affiliation often ensured their loyalty to the colonial project, effectively turning them into internal agents of control over their own people, deepening the political and religious divide within societies.

2. Instrumentalizing Religious Difference: Divide and Rule

The colonial project of "Divide and Rule" frequently leveraged and exacerbated pre-existing or manufactured religious differences, especially between Islam and Christianity, or between different Christian denominations.

A. The Muslim-Christian Divide

In regions with a significant historical Islamic presence (e.g., Northern Nigeria, Sudan, parts of East Africa), colonial administrations employed distinct policies that deepened the fault lines:

-

Indirect Rule through Islamic Structures: In areas with established, centralized Islamic emirates (like Northern Nigeria), the British often practiced Indirect Rule, maintaining the structure of the Emirate but co-opting it to serve colonial interests. Crucially, they sometimes restricted Christian missionary activity in these areas to avoid upsetting the Islamic elite and ensure administrative stability.

-

Targeted Christianization: Conversely, in the more fragmented societies of the South, missionary activity was aggressively promoted. This resulted in a religiously bifurcated political landscape where the North was predominantly Muslim and the South predominantly Christian. Upon independence, these religiously distinct regional identities became a major source of political rivalry and instability, as seen in the ongoing political struggles in Nigeria and Sudan. The strategic use of differential missionary access directly contributed to national disunity.

B. Promoting Ethnic-Religious Proxies

In some cases, colonial powers intentionally linked a specific religion or denomination to a particular ethnic group to create political proxy forces.

-

The Rwandan Example (Hutu-Tutsi): While the division was primarily ethnic and colonial in origin, Christian missionaries often played a role in reinforcing the distinctions. By granting preferential treatment to one group for conversion or education, or by using church institutions to further the colonial racial theories, the Catholic Church in Rwanda inadvertently—or sometimes directly—contributed to the deep-seated political antagonism that later fueled the genocide. This created a situation where religious and ethnic identities became mutually reinforcing political categories.

3. Post-Colonial Political Manipulation

Following independence, African political elites quickly recognized and adopted the colonial strategy of using religion to mobilize support, justify authoritarianism, and neutralize opposition. Religion transitioned from a tool of the external colonizer to a tool of the internal ruler.

A. State-Sponsored Religious Nationalism

Many post-colonial leaders have sought to create a national ideology by adopting or co-opting a dominant religion, often to the exclusion or marginalization of others.

-

Islamization and Exclusion: In countries like Sudan and Somalia, political movements championed Islamization as a means of national unity, but this process often involved enacting Sharia law that systematically discriminated against non-Muslim populations. This directly fuels civil war and secessionist movements (e.g., the separation of South Sudan) as marginalized religious groups fight against the imposition of a state religion. The state uses the language of religious purity to justify political repression against secular or minority religious opponents.

-

The "Chosen" Leader Narrative: Authoritarian leaders frequently employ religious rhetoric to confer a sense of divine mandate upon their rule. They may claim to be specially appointed by God or Allah to lead the nation, making any political opposition not just a civil disagreement, but a sacrilege or betrayal of God's will. This effectively silences dissent by branding opponents as immoral or irreligious.

B. The Weaponization of Prosperity Gospel and Cults of Personality

In contemporary Africa, the rise of powerful, charismatic churches—especially those preaching the Prosperity Gospel—has created a new avenue for political control and division.

-

Legitimizing Wealth and Power: The Prosperity Gospel often teaches that material wealth is a direct sign of God's favor. Political leaders (and the pastors themselves) exploit this by presenting their own wealth and power as a divine blessing. This ideology encourages political passivity among the poor, as they are taught to focus on individual piety and personal financial miracles rather than demanding systemic political change or accountability from their leaders.

-

Politicization of Churches: Highly visible, influential religious figures (megachurch pastors) are often courted by political elites. These pastors, with massive congregations, deliver bloc votes in exchange for political favors, creating a church-state political cartel. This not only divides the electorate along church lines but also directs the focus of social efforts away from broad civic action and toward sectarian, church-specific charity, which can further fragment the social fabric.

4. Religion and Ethnic Conflict: The Interlocking Identities

One of the most insidious ways religion is used to divide is by fusing it inextricably with ethnic identity. When a conflict is framed as a struggle between an "ethnic group A that is Christian" and an "ethnic group B that is Muslim," the political conflict gains a moral and existential dimension, making compromise nearly impossible.

-

The Nigerian Middle Belt: The protracted conflicts in Nigeria’s Middle Belt region are often simplified as "farmer-herder clashes," but the underlying political mobilization frequently uses the Muslim Hausa/Fulani identity against the diverse Christian minority groups. Political entrepreneurs on both sides leverage religious rhetoric to radicalize and mobilize their base, turning disputes over land use into holy wars, thereby using religion to deepen the political, economic, and ethnic divisions.

Religion's utility as a political tool for control and division in African societies is rooted in its ability to provide a comprehensive worldview, a moral justification for power, and a powerful engine for collective mobilization. From the systematic fracturing of traditional authority under colonial Christianization to the post-colonial Islamization projects that marginalize minorities, and the contemporary manipulation of religious figures for electoral gain, religion is frequently deployed to:

-

Create and institutionalize social hierarchies based on adherence to a particular faith.

-

Legitimize authoritarian rule by claiming divine sanction.

-

Weaponize ethnic differences by giving them a religious, existential urgency.

-

Divert attention from political and economic accountability toward moral and spiritual concerns.

While the rhetoric may promote unity under a single, dominant religious banner, the practical effect is often the political and social marginalization of religious minorities and secular citizens, leading to deep, persistent, and often violent division that undermines the stability and collective well-being of the entire society.

Religion's role in African societies is a profound duality, acting both as a source of deep communal unity and as a potent political instrument for control and division. Rather than solely uniting diverse populations, its manipulation—first by colonial powers and later by post-colonial elites—has successfully fractured societies, cemented social hierarchies, and exacerbated ethnic conflict. The effect has been a persistent undermining of national cohesion and the rule of law across the continent.

1. The Colonial Blueprint: Christianization and the Creation of a Divided Elite

The colonial project strategically deployed Christianity as a primary tool to dismantle indigenous political structures and implement its "Divide and Rule" strategy.

A. Undermining Traditional Authority

Colonial administrations worked in concert with missionary societies to delegitimize Indigenous African Religions (IARs), branding them as "primitive" or "pagan." This was not just a cultural act; it was a political necessity for conquest.

-

Political Vacuum: Traditional African governance, often intertwined with spiritual authority (e.g., through ancestral veneration or sacred kingship), lost its moral and political legitimacy upon the introduction of a new, "superior" foreign faith. By promoting conversion, colonizers stripped local leaders of their spiritual authority, thereby weakening any organized resistance to European rule.

-

Cultural Fragmentation: Conversion required a rejection of traditional customs, creating an immediate and often hostile rift within families and communities—between the converted and the traditionalists—which fragmented pre-existing social bonds essential for communal action and political solidarity.

B. Creating a Subordinate, Religious Elite

Mission schools were the engine of this division. They educated a new class of African elites, but access was often conditional on religious conversion.

-

The "Christian" Advantage: Converts gained preferential access to literacy, civil service positions (clerks, interpreters), and resources, resulting in a religiously-defined socio-economic hierarchy. This created a small, influential class politically loyal to the colonial masters because their status and power were entirely dependent on the new, religiously-sanctioned colonial order. This new elite had little in common with the uneducated, non-Christianized majority, creating a deep class and cultural chasm.

-

Reinforcing the Muslim/Christian Schism: In religiously mixed regions, like Nigeria, colonial policies often intensified the existing divide between Islam and Christianity. In parts of the North, the British implemented Indirect Rule through established Islamic structures and often restricted Christian missionary activity to maintain the loyalty of the powerful Muslim elite. Conversely, Christianization was aggressively promoted in the South. This selective patronage created a religiously-bifurcated political map which, at independence, became the foundation for bitter regional and national-level political competition and distrust.

2. Post-Colonial Instrumentalization for Authoritarianism

Upon achieving independence, African political leaders quickly adapted the colonial playbook, using religion not for national unity but for personal power consolidation and the suppression of democracy.

A. State-Sponsored Religious Nationalism

Rulers often co-opted the dominant religion to forge a national ideology, justifying their rule and marginalizing opposition.

-

Divine Mandate and Repression: Authoritarian leaders, from presidents to military juntas, frequently employ religious rhetoric to confer a "divine mandate" on their power, making opposition seem not only political but also a spiritual transgression. This is particularly effective in silencing dissent and justifying repression against secular or minority religious groups.

-

Islamization and Secession: In countries like Sudan, political elites pursued aggressive Islamization policies, imposing Sharia law that disenfranchised and persecuted non-Muslim populations. This deliberate use of religion to define citizenship and legal rights was a core driver of the long civil war and ultimately led to the political separation of South Sudan, illustrating how state-sponsored religious identity is a direct engine of national division.

B. The Politicization of the Pulpit

In contemporary Africa, the rise of powerful, politically connected charismatic Christian movements, such as those preaching the Prosperity Gospel, has added a new layer of control and division.

-

A "Prosperity" Distraction: This theological movement often focuses individual piety and personal wealth generation, teaching followers to be passive toward systemic political corruption. By presenting a leader's wealth and success as a sign of divine favour, it legitimizes the status quo of the political elite and encourages the poor to wait for a personal miracle rather than demand political accountability.

-

Electoral Bloc-Building: High-profile religious leaders with massive followings (megachurch pastors, influential imams) become key political brokers, delivering huge, organized voting blocs to political candidates in exchange for influence and state favours. This politicizes faith organizations and segments the electorate along denominational lines, creating an environment where a politician’s religious identity, rather than their competence, becomes the primary factor for political mobilization, further dividing the citizenry.

3. Religion as an Accelerator of Ethnic Conflict

Perhaps the most destructive manifestation is the intentional fusion of religious identity with ethnic grievances, turning socio-economic conflicts into existential, totalizing "religious wars."

-

The Nigerian Conflict Trajectory: Conflicts in Nigeria are often framed politically along the lines of the predominantly Muslim North and the predominantly Christian South and Middle Belt. Politicians on both sides exploit these religious identities to mobilize their base, turning disputes over land (e.g., between Muslim herders and Christian farmers) into politically-charged ethno-religious wars. By weaponizing religion, political entrepreneurs are able to generate much greater levels of violence, hatred, and mobilization than a simple ethnic or economic conflict would achieve, deepening the national cleavage and making sustainable peace elusive.

-

The Central African Republic (CAR): The violence in the CAR, although rooted in political and economic competition, quickly took on a stark religious veneer with the anti-Balaka (predominantly Christian) and Séléka (predominantly Muslim) groups. Political leaders on both sides leveraged religious labels to mobilize forces and justify horrific acts of violence, demonstrating how religion can be instrumentalized to provide a moral and collective identity for political-military action, thereby polarizing the entire nation into warring religious factions.

In conclusion, the history of religion in African politics shows a consistent pattern: it is used as a mobilizing factor for exclusive political gain rather than inclusive social good. By creating and exploiting divisions—whether colonial-era hierarchies, post-colonial state-sponsored sectarianism, or the fusion of faith and ethnic rivalry—political actors transform a spiritual domain into a material tool that achieves control by actively fracturing the societies it purports to save.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Seguridad

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Juegos

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture