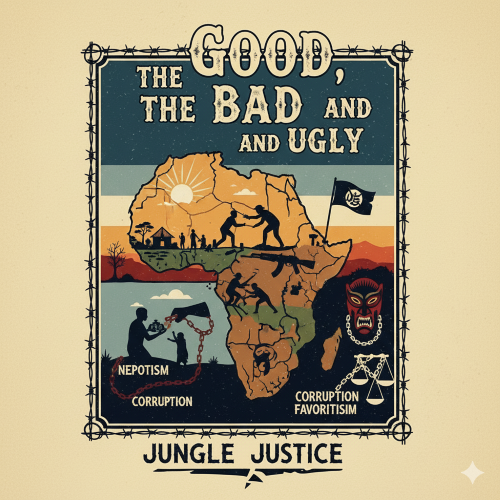

Why do ethnic loyalties often trump national interests in African societies?

“When Loyalty to Tribe Betrays Our Shared Humanity”

-

What happens when personal kinship outweighs justice and competence?

-

Examine cases in politics and public service where favoritism undermined meritocracy. Show consequences for communities.

Why Ethnic Loyalties Often Trump National Interests in African Societies-

The Paradox of Unity in Diversity-

Africa is a continent of nations within nations — where the map tells one story, but the heart tells another. Beneath the flags, constitutions, and national anthems lie hundreds of ethnic identities that define how people see themselves and one another. These identities — rooted in language, kinship, ancestry, and tradition — predate colonial states by centuries. Yet in modern Africa, they frequently undermine the very national projects that leaders and citizens alike claim to serve.

Why do ethnic loyalties so often override national interests? The answer lies in a combination of history, governance, inequality, and psychology. When state institutions fail to embody fairness, when politics becomes a winner-takes-all game, and when belonging to a tribe offers security that the nation does not, people naturally choose kin over country.

1. Colonial Origins: Nations Without Foundations

The origins of Africa’s ethnic politics lie in the arbitrary borders drawn by European colonizers during the 1884–85 Berlin Conference. The colonial project merged distinct ethnic groups into single political units with little regard for their cultural or historical relationships. Nigeria, for example, was an artificial creation that brought together over 250 ethnic groups — including the Hausa-Fulani in the North, the Yoruba in the West, and the Igbo in the East — under one flag.

Colonial administrators, instead of fostering unity, deepened ethnic divisions as a strategy of control. Britain’s “divide and rule” policy relied on local chiefs and traditional structures to maintain order. In practice, this meant elevating certain groups over others, granting them access to education, jobs, and power. In Kenya, the Kikuyu benefited more from mission schools and economic opportunities than the Luo or Kalenjin. In Rwanda, the Belgians favored the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority, sowing the seeds for future genocide.

When independence came in the 1950s and 1960s, these new African nations inherited borders and administrative systems designed for exploitation, not unity. The absence of a shared precolonial national identity meant that ethnic loyalty remained the most authentic form of belonging.

2. Weak State Institutions and the Failure of Trust

In societies where the state is weak, citizens often turn to ethnic networks as their most reliable source of support. Many African countries lack robust institutions capable of delivering justice, education, healthcare, or economic opportunity equally across all regions. When the state is seen as corrupt, biased, or captured by one ethnic elite, people stop seeing it as their government.

For example, in Nigeria, political offices are often distributed through the “federal character” principle — meant to ensure representation for all ethnic groups. Yet in practice, this system often reinforces suspicion: each group fears marginalization and seeks to place “its own people” in key positions. Citizens come to view national institutions not as neutral arbiters, but as battlegrounds for ethnic advantage.

The same dynamic appears across Africa. In Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and Ethiopia, public service appointments, scholarships, and contracts are frequently allocated along ethnic lines. This creates a vicious cycle: the more the state favors one group, the less legitimacy it has among others. Trust — the invisible glue that binds citizens to a nation — erodes, and people retreat into ethnic loyalty for protection.

3. The Politics of Patronage: When Power Feeds the Tribe

African politics often operates through patron-client networks, where leaders distribute public resources in exchange for loyalty. Because elections and government positions are seen as gateways to wealth, each ethnic group pushes to have “one of their own” in power. Once in office, leaders reward their base — building roads, schools, and hospitals in their home regions, or appointing allies from their ethnic group to strategic posts.

This is not simply greed; it’s a survival mechanism in a system that lacks accountability. When citizens believe that power will be used to favor one’s tribe, they vote defensively — not for ideology or policy, but for ethnic security. In such a system, “our man in power” becomes a protector of communal interests.

The result is that national politics becomes a zero-sum game. Elections resemble ethnic censuses, and development becomes politicized. The Nigerian saying captures it perfectly: “When my tribe’s man is in power, it is our turn to eat.”

This mentality is not unique to Nigeria. In Kenya, the 2007–2008 post-election violence erupted when communities believed that power had been stolen from their ethnic group. In South Sudan, the Dinka–Nuer rivalry within the ruling elite plunged the world’s youngest nation into civil war barely two years after independence. Across Africa, political competition becomes a contest between ethnic blocs rather than an exchange of ideas.

4. Historical Grievances and Uneven Development

Ethnic loyalties also persist because of deep-seated historical grievances and inequalities. Colonial and postcolonial governments often favored certain regions economically, leaving others underdeveloped. In Nigeria, the oil-rich Niger Delta has long complained of exploitation and environmental neglect by the central government dominated by elites from other regions. In Cameroon, the Anglophone minority feels marginalized by the Francophone majority. In Ethiopia, the Tigrayans’ long dominance over national institutions fueled resentment among other ethnic groups, culminating in the 2020–2022 civil war.

When communities perceive that they are consistently excluded from power or resources, ethnic solidarity becomes an act of resistance. Loyalty to one’s group becomes synonymous with justice, while national unity feels like a disguise for oppression. Thus, instead of seeing themselves as citizens of a shared nation, people define themselves as members of oppressed or privileged tribes struggling for balance.

5. Psychological Comfort and the Search for Belonging

At its core, ethnicity fulfills a human need for identity, belonging, and protection. In societies marked by instability and insecurity, people naturally turn to their most familiar and trustworthy networks — family, clan, and tribe. The tribe becomes a psychological fortress in a world where the state cannot be trusted.

When the nation fails to provide safety, fairness, or hope, ethnic identity offers meaning. It is emotional, not merely rational. People trust those who speak their language, share their customs, and understand their history. Ethnic solidarity is not always about hatred for others; it is often about fear — fear of being left out, dominated, or forgotten in an unfair system.

6. The Role of Elites and Political Manipulation

Ethnic divisions persist because political elites actively exploit them. When leaders lack developmental vision or moral legitimacy, they weaponize ethnic sentiment to rally support. Instead of building inclusive narratives, they portray themselves as defenders of their people against rival groups.

In many African elections, campaign rhetoric centers on ethnic fearmongering — warnings that “the other tribe will dominate us” or “they will take your jobs.” These tactics keep citizens emotionally attached to ethnic identities and distracted from systemic corruption or economic failure.

This manipulation works because it taps into historical trauma and present-day insecurity. The elite’s ethnic appeal becomes a shortcut to power — cheaper and more effective than genuine policy reform. The tragedy is that ordinary people, not the elites, pay the price in the form of division, violence, and underdevelopment.

7. The Consequences: A Fractured National Consciousness

When ethnic loyalty overrides national interest, governance suffers. Meritocracy gives way to favoritism. National projects stall because every group demands its “share.” Civil service becomes bloated with political appointees, and corruption thrives under the shield of ethnic defense.

Worse still, national identity becomes hollow. Citizens may sing the anthem or wave the flag on Independence Day, but their real loyalty lies elsewhere. In times of crisis, such as elections or economic downturns, the fragile national fabric unravels quickly. Civil wars, coups, and secessionist movements — from Biafra in Nigeria to Eritrea, South Sudan, and Tigray — all trace their origins to unresolved ethnic fractures.

8. The Way Forward: Building Nations, Not Just States

The solution is not to suppress ethnic identity but to create systems where national and ethnic loyalties complement rather than compete.

-

Strong Institutions: Building impartial institutions that deliver justice, services, and opportunities to all citizens reduces the need for ethnic fallback.

-

Inclusive Leadership: Political leaders must represent the entire nation, not their tribe. Power-sharing mechanisms should reward diversity without entrenching division.

-

Civic Education: Schools and media must cultivate national consciousness — teaching shared history and values that transcend tribe.

-

Economic Equity: Balanced regional development and fair resource distribution can heal historical wounds.

-

Cultural Dialogue: Encouraging inter-ethnic exchange, marriages, and cultural collaboration strengthens mutual understanding.

Nation-building requires more than borders and constitutions — it demands emotional investment. Citizens must feel that their nation protects and represents them more effectively than their tribe ever could.

From Tribal Fear to National Faith

Ethnic loyalty trumps national interest not because Africans are inherently tribal, but because the systems meant to bind them as nations have often failed. Where the state is weak, unjust, or exclusive, the tribe becomes the only structure of trust.

The challenge of modern Africa is to reverse that equation — to make the nation the most trusted, protective, and dignifying identity a person can hold. The journey from ethnic loyalty to national faith will not happen overnight, but it begins with leadership that serves all citizens equally, and with people who dare to imagine a community broader than their bloodline.

As the proverb says, “When there is no enemy within, the enemies outside cannot harm you.” Africa’s true unity will begin the day its citizens see one another not as rivals of different tribes, but as partners in the same dream — the dream of a continent finally free from the ghosts of its divisions.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Ασφάλεια

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Παιχνίδια

- Gardening

- Health

- Κεντρική Σελίδα

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- άλλο

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture