Is the Rise of Boko Haram and ISWAP More a Symptom of Failed Governance Than the Religion Itself?

"Ubuntu Rooted in Humanity"

When people around the world hear of Boko Haram or ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province), the images that often come to mind are those of masked men, black flags, suicide bombings, and the cry of “Allahu Akbar.” The instinctive conclusion is that these groups are the product of radical religion — a violent distortion of Islam. Yet, beneath the loud surface of jihadist slogans lies a deeper, quieter truth: the roots of Boko Haram and ISWAP are political and social failures wearing religious clothing.

Their rise is not just about ideology but about a systemic collapse of governance, where poverty, corruption, and neglect left millions feeling abandoned by the very state meant to protect them. Religion, in this sense, became the language of protest and identity — not the original disease, but the mask through which anger found expression.

To understand this, one must look beyond the bombs and verses to the broken promises and forgotten people of northern Nigeria and the Lake Chad region.

1. The Soil of Despair: Governance in Northern Nigeria

Northern Nigeria, the birthplace of Boko Haram, has for decades been a symbol of inequality. While the country’s oil wealth flows from the south, the north has languished in underdevelopment. According to Nigerian government data and international reports, northern states like Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa rank lowest in education, health, and income.

-

Over 70% of people in Borno State live below the poverty line.

-

Illiteracy exceeds 60% among youth in some northern areas.

-

Access to healthcare and safe water is among the worst in the country.

This is not just economic poverty — it is institutional neglect. Decades of corrupt governance and political manipulation have drained local institutions of trust. When schools fail, roads crumble, and officials enrich themselves, citizens begin to question what the state even stands for.

In such an environment, any group promising justice, dignity, and moral order can find followers. Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf, exploited precisely this vacuum. In the early 2000s, he began preaching not violence but reform — attacking government corruption and Western-style education, which he claimed was designed to perpetuate moral decay and inequality.

To the poor and disillusioned, his message made sense: the elites were corrupt, the system was unjust, and only divine law could restore balance. The movement’s later descent into terrorism was fueled by a brutal response from the state and the same structural failures that had created the movement in the first place.

2. The Spark: Repression, Not Religion

The turning point came in 2009, when Nigerian security forces clashed with Yusuf’s followers in Maiduguri. Hundreds of his members were killed, and Yusuf himself was executed extrajudicially by police. Instead of eliminating the movement, the government’s violent overreach poured fuel on the fire.

What began as a religious reformist movement transformed into a vengeful insurgency. Yusuf’s followers reorganized under Abubakar Shekau, adopting a far more violent ideology and declaring war on the Nigerian state.

This pattern — repression without reform — reflects the broader crisis of governance in Nigeria. The government’s approach to dissent has often been militarized rather than developmental. When young people demand jobs or fairness, they are ignored; when they protest, they are silenced. In this environment, violence becomes the only language the forgotten feel will be heard.

Thus, Boko Haram’s radicalization was less about theology and more about political exclusion and state brutality. The state’s failure to deliver justice became its own indictment.

3. The Empty Classroom: Education, Ignorance, and Manipulation

The very name “Boko Haram” translates loosely to “Western education is forbidden.” While that phrase has been misinterpreted as pure religious extremism, it reflects something deeper — a crisis of education and identity.

In northern Nigeria, Western education was historically seen as a colonial imposition that alienated youth from their culture and faith, while the government-run schools that replaced traditional Islamic learning were often underfunded and ineffective. Many children grew up in Qur’anic schools (Almajiri system), where they memorized scripture but lacked modern skills or job prospects.

This produced generations of spiritually aware but economically powerless youth — a perfect target for extremist recruiters.

When governance fails to educate, ignorance becomes a weapon. Boko Haram exploited this, offering a perverse form of “education” that replaced critical thinking with indoctrination. The state’s neglect of its young became a silent recruitment campaign for those who promised a new moral and social order.

In truth, the problem was never that Islam rejected education; it was that the government failed to provide education worth having.

4. Poverty as a Political Weapon

Across the Lake Chad Basin, poverty has been both the cause and the consequence of extremism. In communities where a farmer earns less in a month than a politician spends on a weekend, the appeal of militant movements grows.

Boko Haram and later ISWAP capitalized on this inequality by offering what the state could not:

-

Small stipends to recruits.

-

Loans to traders under “Islamic charity.”

-

A sense of belonging and purpose.

In some captured areas, ISWAP even introduced its own governance structures — collecting taxes, settling disputes, and distributing food. Ironically, many locals reported that these militants were more disciplined and predictable than the corrupt officials who had once ruled them.

Such comparisons reveal the depth of Nigeria’s governance failure. When citizens see a terrorist group as more reliable than their government, the problem is not religion — it is the collapse of legitimacy.

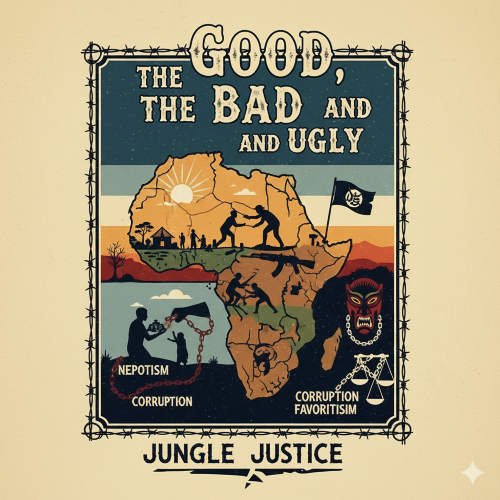

5. Corruption: The Fertilizer of Extremism

Nigeria’s fight against Boko Haram has been undermined repeatedly by corruption within the security and political establishment. Billions of naira allocated for defense have been siphoned off through inflated contracts and fake arms deals. Soldiers on the front lines often lack basic equipment, food, or pay.

This corruption not only weakens military capacity but also sends a dangerous message: the war itself is a business. Communities under threat lose faith in a government that appears more interested in enriching itself than in saving lives.

Meanwhile, politicians exploit religious divisions for electoral gain, framing conflicts in sectarian terms to distract from governance failures. Religion becomes the scapegoat of corruption, while the real culprits remain untouched.

6. ISWAP and the Evolution of Disillusionment

When ISWAP split from Boko Haram in 2016, it was not merely an ideological shift but a reaction to Shekau’s brutality and leadership failures. ISWAP’s commanders accused him of killing fellow Muslims and mismanaging resources.

Unlike Boko Haram’s chaotic violence, ISWAP sought to build a more organized structure — collecting taxes, enforcing a harsh version of Sharia, and trying to “govern” captured territories. In their propaganda, they portrayed themselves as a purer, more disciplined alternative to Nigeria’s corrupt state.

While still violent and oppressive, ISWAP’s rise demonstrates how the vacuum of governance breeds parallel systems of power. People in the Lake Chad region who had lost all trust in Abuja’s government often cooperated with ISWAP out of survival, not faith.

The tragedy is that the same forces that failed to build roads, schools, and justice in peacetime are now fighting endless wars against the monsters they helped create.

7. Religion as a Mirror, Not the Motive

Religion has always been a double-edged sword in African societies — capable of inspiring compassion or manipulation. Boko Haram and ISWAP do not represent Islam any more than corrupt politicians represent democracy.

Their use of faith is instrumental, not spiritual. They wrap their anger in verses and prayers, but their actions — kidnapping, killing, enslaving — violate the very principles they claim to defend. Religion is merely the vehicle through which deeper political and social failures travel.

At the heart of it all lies a crisis of governance, justice, and belonging — problems that cannot be solved by bombs or sermons alone.

8. The Path Forward: Rebuilding Trust through Ubuntu

To defeat extremism, Nigeria and its neighbors must move beyond a purely military approach. The fight against Boko Haram and ISWAP must be won in classrooms, hospitals, and local councils — not just in battlefields.

That means:

-

Rebuilding education to give every child a future beyond extremism.

-

Restoring justice by holding corrupt leaders accountable.

-

Investing in rural development, where most recruitment takes place.

-

Empowering local communities to govern themselves with dignity.

-

Promoting Ubuntu — shared humanity — across ethnic and religious lines, reminding people that the enemy is not faith, but the system that divides and devalues human life.

Only when governance becomes a reflection of fairness, not favoritism, will the appeal of groups like Boko Haram and ISWAP fade.

9. The True Face of the War

The rise of Boko Haram and ISWAP is not a story of religion gone mad; it is a story of a nation’s broken social contract. When governance fails to protect, educate, and uplift its citizens, extremists rush in to fill the void.

Religion, in this case, is the symptom — failed governance is the disease. The cure will not come from more guns or slogans but from justice, opportunity, and empathy.

In the spirit of Ubuntu, Africa must remember: we are only as strong as the humanity we extend to our weakest. And when governments abandon their people, faith becomes a refuge — and sometimes, a rebellion.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Beveiliging

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Spellen

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture