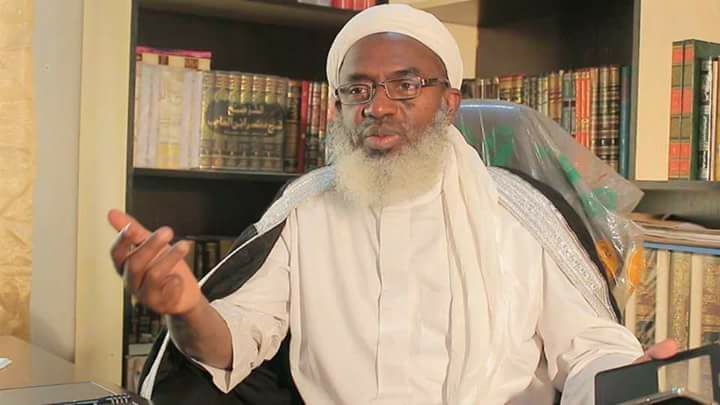

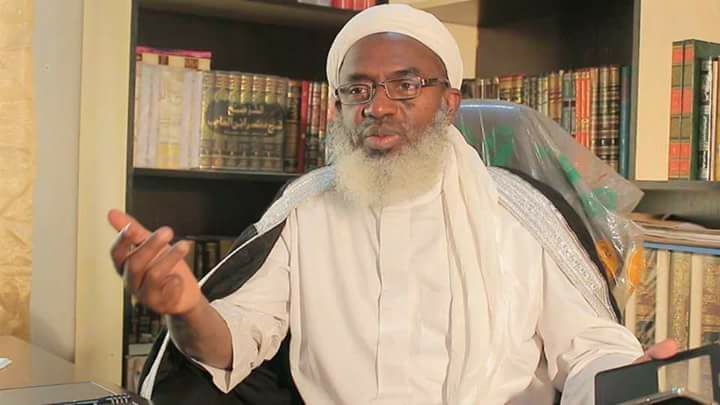

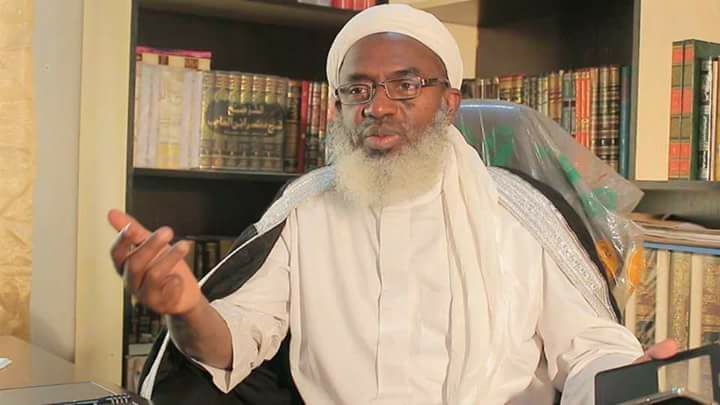

Terrorist agent Sheikh Ahmad (Ahmad Abubakar) Gumi and his activities related to Nigeria’s banditry / extremist landscape.

-

Who he is: Ahmad Abubakar Gumi is a Kaduna-based Islamic cleric, a trained medical doctor and retired Nigerian Army captain, and the son of the late influential cleric Abubakar Gumi.

What he has done (activities)

-

Mediation with “bandits” / kidnappers: Since early 2021 Gumi has travelled into forests and bandit camps in northwest Nigeria to preach, negotiate and secure releases of hostages. He describes this as a peace/rehabilitation mission and has publicly said some fighters he met “repented” and stopped kidnapping. Several media reports document his direct contacts with groups accused of mass abductions.

-

Advocacy for dialogue/amnesty: He has repeatedly urged the federal and state governments to open dialogue and explore amnesty or negotiated settlements rather than purely military responses — a view that has informed his direct outreach to armed actors.

Controversies and criticisms

-

Accusations of being too close to criminals / “apology for terrorism”: Critics — including civil society groups and commentators — say his public sympathy for bandits and his willingness to meet them risks legitimizing criminals and could amount to apologising for violent actors. Some called for investigation or prosecution for statements seen as defending or normalizing banditry.

-

Security-service attention / disputed summons: Reports circulated in 2021 that Nigeria’s security services (DSS / SSS) had summoned or invited Gumi for questioning over his comments and contacts. Gumi publicly denied being arrested or formally detained in at least one instance; reporting shows the government took notice and at times rebuked his public comments.

-

Concerns about extremist links in the broader context: Independent research and journalistic analyses show that some bandit groups in the northwest have become entangled with jihadi groups (Boko Haram/ISWAP) in ways that blur lines between “banditry” and organized extremist violence — which raises alarm when public figures engage with armed groups without clear safeguards. (This is a contextual point rather than a direct proven link between Gumi and specific terrorist organizations.)

Recent / notable developments

-

Administrative actions (2025 Hajj ban reporting): Nigerian and regional reporting indicated Saudi authorities barred Gumi from performing the 2025 Hajj and deported him from the airport; local outlets covered that incident. (This is a recent administrative/deportation-type report rather than a criminal charge in Nigeria.)

Mixed record: Reporting shows Gumi is a high-profile, polarizing figure who frames his actions as peacemaking and religious outreach — and some hostage releases have been credited to negotiations in which he played a role. At the same time, many security analysts, victims’ families, civil society and politicians view his approach as dangerously permissive or as giving political cover to violent actors. The situation is made more complex by real overlaps between criminal bandits and jihadist groups in parts of northern Nigeria.

The Face of A Terror Orginiser in The Northern Nigeria- Supported and sponsored by some Nothern political elites in Nigeria.

Sheikh Ahmad Gumi (selected, 2021–2025)

June 2021 — Public outreach into bandit areas / media attention.

Gumi began receiving wide attention for travelling into forests and meeting with suspected “bandits” and kidnappers, positioning his visits as preaching, mediation and attempts to secure hostage releases. Videos and reports showing him speaking to armed groups circulated in Nigerian media.

25–26 June 2021 — SSS/SSS invitation and public dispute.

After publicly making claims about security-force conduct in the northwest and describing bandits’ grievances, reports said Nigeria’s State Security Service (SSS/DSS) invited him for questioning; Gumi publicly denied being “summoned” or arrested but confirmed being contacted. This episode produced intense public debate about his role.

2021–2022 — Negotiation role and hostage-release efforts (documented cases).

Multiple reports credit negotiations and confidence-building contacts (including Gumi’s visits) with helping secure releases of some abductees in northwest states; Gumi framed this as pastoral/spiritual rehabilitation and advocacy for dialogue rather than force. Analysts and journalists documented both some releases and concerns about legitimisation of criminals.

2021–2022 — Influence in bandit areas; possible impact on local leaders (analyst assessment).

Security analysts (including a West Point/CTC study) reported that Gumi’s pastoral visits and deployment of clerics/Islamic texts into bandit-controlled areas appear to have influenced some bandit leaders’ public posturing and local legitimacy — the paper specifically notes Gumi’s visits to areas linked to powerful leaders (including references to Turji’s area) and argues his activities had measurable local effects. (This is an analytical assessment rather than a claim of criminal collusion.)

2022 — Public advocacy for dialogue / amnesty; political comments.

Gumi repeatedly urged governments to open dialogue and pursue negotiated settlements or amnesty-like solutions for some bandit groups; he also made political comments warning communities about electing leaders who would not address the crisis — statements that drew both support from some local leaders and sharp criticism from others.

2021–2024 — Repeated public criticism and legal/political pushback.

Civil society groups, victims’ families, lawyers and commentators repeatedly criticised Gumi’s public sympathy for bandits and urged formal investigations or for the government to distance itself from his mediation approach. Legal commentators at times labelled certain public comments as dangerously close to “apology” for terrorism and called for accountability.

May–June 2025 — Saudi Arabia bars / deports Gumi from Hajj delegation.

In May 2025 Saudi authorities denied him entry to perform the Hajj and reportedly deported him from the kingdom despite an issued visa; Nigerian outlets covered his statement and reactions from rights groups and some local commentators. This was widely reported as an administrative action by Saudi authorities rather than a Nigerian criminal charge.

Notes on sources and interpretation

-

What is well documented: Gumi’s public visits to forest/bandit areas, his self-described mediation/rehabilitation role, several cases where negotiators (including religious figures) helped secure releases, the SSS/press exchanges in mid-2021, and the 2025 Saudi administrative denial of Hajj entry. These items are supported by multiple Nigerian media outlets and at least one academic/analyst report.

-

What remains debated or analytical: Whether Gumi’s outreach directly enabled criminal activity or whether it reduced violence in specific pockets is contested. Some analyst pieces caution that religious mediation can produce short-term releases but also risk legitimising violent actors; other observers defend engagement as a pragmatic route to saving lives. The West Point/CTC analysis is a good example of a careful, sourced assessment of those tradeoffs.

Sheikh Ahmad Abubakar Gumi

Executive summary-

Sheikh Ahmad Gumi is a high-profile Kaduna-based Islamic cleric who since 2021 has engaged directly with armed “bandit” groups in north-west Nigeria, presenting himself as a mediator and spiritual rehabilitator. His interventions have produced some hostage releases and public attention — but also strong allegations that his outreach legitimises violent actors, repeated scrutiny by Nigerian security agencies, and (most recently) administrative action by Saudi authorities barring him from the 2025 Hajj.

1) Major public allegations (what critics claim)

-

Normalising / legitimising criminals. Critics (victims’ families, civil-society groups, commentators) argue Gumi’s public engagement and language — calling for dialogue or amnesty — risk legitimising kidnappers and bandits and may weaken the case for prosecution. This is the central political allegation repeated across Nigerian commentary.

-

Providing apologias or sympathy for violent actors. Some public statements by Gumi (for example, comparing certain security failures and raising the grievances of fighters) were characterised by opponents as sympathetic to perpetrators or as “apologising” for criminal violence.

-

Operational risk: contact with militants who have jihadist ties. Analysts warn that northwest “bandit” groups have at times overlapped with jihadist actors (Boko Haram/ISWAP splinters), so high-profile contact with bandits carries the reputational and security risk of tangling with extremist networks. (This is an analytical concern rather than an allegation that Gumi is an extremist agent.)

2) Gumi’s denials and stated position (what he says)

-

Denies wrongdoing and frames actions as pastoral/peacemaking. Gumi says his visits into forests were done with security awareness and with the aim to preach, persuade fighters to repent, and secure hostage releases. He has repeatedly denied illegal collaboration and has said security agencies knew of or accompanied aspects of his outreach.

-

Advocates negotiated solutions and amnesty for some fighters. He publicly argues for engagement and political/policy solutions (dialogue, rehabilitation or amnesty where appropriate) rather than only kinetic responses. He presents this approach as pragmatic and life-saving in hostage situations.

3) Documented security-service / government actions and responses

-

Mid-2021 — SSS/DSS invitation for questioning (June 2021). Nigerian intelligence/security services publicly confirmed they invited Gumi for questioning after he accused security personnel of colluding with bandits; Gumi publicly disputed reports that he had been detained, saying he was not arrested. The episode generated significant national debate.

-

Repeated public rebukes and calls for investigation (2021–2024). Various actors (army spokespersons, civil-society groups, lawyers, politicians) publicly criticised Gumi’s comments and urged investigations or clearer government positioning. Media records show multiple instances of public pushback and scrutiny rather than a single, sustained criminal prosecution.

-

May 2025 — Saudi administrative action: barred/deported from Hajj. Saudi authorities reportedly denied him entry and deported him from the kingdom in May 2025, barring him from performing the 2025 Hajj; Nigerian outlets covered the incident as an administrative decision by Saudi authorities rather than a Nigerian criminal conviction.

4) Independent analyst assessments (what researchers / think tanks say)

-

Complex, mixed outcomes from religious mediation. Security scholars and policy analysts emphasise that religious mediation can sometimes secure short-term humanitarian gains (hostage releases), but it may also grant actors local legitimacy and complicate longer-term enforcement and accountability. Research on the region stresses trade-offs between saving lives and avoiding legitimisation.

-

Bandit–jihadist overlap magnifies risk. Analysts at institutions studying violent extremism have documented evidence of “jihadization” of some bandit networks (fighters or cadres moving between criminal and ideological violence), which makes any high-profile contact with bandit leaders a potential vector for extremist influence or narrative laundering. Analysts therefore call for careful safeguards, transparency, and coordination with security agencies if mediators engage armed groups.

5) Evidence of impact (what’s demonstrable in public reporting)

-

Hostage releases and publicised meetings. Multiple media reports say Gumi’s contacts coincided with some releases of abductees; these are typically reported as negotiated outcomes where clerics, negotiators or local intermediaries played a role. These outcomes are sometimes cited by Gumi’s supporters as vindication of his approach. (Media coverage documents individual release events; the causality/long-term effect is debated.)

-

No widely publicised criminal conviction. Public records and mainstream reporting to date do not show a criminal prosecution or conviction of Gumi on terrorism charges in Nigeria; government responses have tended to be invitations to speak to security services, public rebukes, or, in the Saudi case, administrative denial of entry.

6) Assessment — strengths, risks, and open questions

Strengths / pragmatic case for engagement

-

Religious mediators can access fighters in places state actors cannot reach, sometimes securing hostage releases and opening channels for demobilisation. Gumi’s supporters point to documented releases as proof of value.

Risks / reasons for caution

-

Contact risks normalising violent actors, creating perverse incentives (kidnappers may see negotiation as a revenue route), and inadvertently amplifying extremist narratives if the groups have jihadist links. The bandit–jihadist overlap in NW Nigeria is a documented phenomenon and changes the risk calculus for engagement.

Open questions / gaps in public record

-

The precise operational terms (who pays ransoms, who arranges security during visits, what guarantees are given) of many negotiations remain opaque in public reporting.

-

To date, public reporting documents invitations to security services and administrative actions (Saudi deportation) but no criminal convictions — raising questions about whether formal investigations were completed or closed.

Banditry in NW Nigeria generally refers to criminal violence motivated by economic gain, local grievances, or survival, rather than ideology. Key characteristics:

-

Kidnapping for ransom, cattle rustling, village raids.

-

Loose organization: bandit groups are often decentralized, fragmented, and led by “warlords” rather than a unified political/ideological movement.

-

Root causes: poverty, unemployment, porous borders, weak state presence.

Terrorism, by contrast, involves ideologically driven political violence. In the Nigerian context, this often means jihadist insurgent groups:

-

Groups like IS-linked or al-Qa‘ida–linked jihadists (e.g. ISGS, JNIM) operate in or influence the region.

-

Their objectives are often political/religious (e.g. establishing a caliphate, imposing ideological rule), not just financial gain.

-

They may cooperate with criminals, but they have distinct strategies and motivations.

2. The “Crime–Terror Nexus” in NW Nigeria

Analysts have documented a complex relationship between bandits and jihadist groups in NW Nigeria. Key points:

-

According to James Barnett et al. (West Point / CTC), while there is some cooperation (e.g., exchange of training or tactical advice), there is not necessarily a full ideological conversion of bandits to jihadis.

-

They argue that bandits are often too politically unambitious (from a jihadist-ideological perspective) and too fractured to be easily co-opted.

-

However, jihadi groups have exploited the instability created by bandits: they use the chaos, weak governance, and “ungoverned spaces” to establish enclaves or logistical footholds in the region.

-

Other analysts (e.g., The Soufan Center) note that jihadist factions are actively recruiting among Fulani herdsmen (a community where many bandits come from), suggesting a growing convergence.

-

Yet, some research (e.g., Hudson Institute) argues that most bandits remain primarily criminals rather than ideological militants.

3. Legal & Ethical Implications

-

Scholars like Alex Abang Ebu argue that the response to banditry requires a hybrid legal and security strategy (not just counterterrorism) because banditry is not purely ideological.

-

There are legal challenges: existing Nigerian legal frameworks were not always built to distinguish easily between “terrorists” and “criminals,” especially in rural, under-governed areas.

-

Some argue that treating all bandits as terrorists risks over-militarization, potentially harming local communities and exacerbating underlying grievances.

4. Where Sheikh Gumi’s Actions Fit In

-

Mediation & Negotiation Role: Gumi’s engagement with “bandits” aligns more with a conflict-management / peacemaking approach rather than ideological engagement. He often frames his work in spiritual or pastoral terms, seeking to rehabilitate or persuade rather than to recruit to a jihadist cause.

-

Risk from the Crime–Terror Nexus: Because of the overlap between some bandit groups and jihadists, his contact with bandit leaders carries potential strategic risks. Analysts would worry that mediation could indirectly empower actors who have links (or become useful) to jihadist networks.

-

Legitimacy Trade-Offs: Supporting dialogue with bandits could reduce violence short-term (e.g., hostages released), but it could also provide them with political or social legitimacy, undermining efforts to dismantle violent networks — especially if some of these networks have extremist dimensions.

5. Reflection

-

The distinction between banditry and terrorism in NW Nigeria is not clear-cut. While many actors are primarily criminal (bandits), there is a growing and non-trivial overlap with jihadist movements.

-

Mediation or negotiation (such as that pursued by Gumi) can deliver humanitarian benefits, but it must be handled with care given the risk of legitimizing or strengthening criminal–ideological actors.

-

Policymakers, scholars, and security agencies must balance short-term gains vs. long-term risks: engaging bandits pragmatically yet ensuring that any engagement does not inadvertently facilitate extremist consolidation.

Where Is Sheikh Gumi Now — Current Status (2025)

-

Deported from Saudi Arabia to Nigeria

-

In May 2025, Saudi authorities denied him entry to perform the Hajj, despite him having a visa, and subsequently deported him to Nigeria.

-

According to a Nigerian government / Hajj Commission source, this was a deliberate “entry restriction” rather than a simple visa issue.

-

-

Back in Nigeria

-

After deportation, Gumi returned to Nigeria and reportedly resumed his teaching and religious duties.

-

He has stated publicly that he is now “free to attend to … health and farming activities” in Nigeria.

-

He’s also made statements criticizing Saudi Arabia’s restrictions, calling the country “a police state” and saying his ban was due to his political views.

-

-

Base of Operations

-

He continues to be associated with Kaduna, Nigeria, where he has long been based.

-

He holds a role at the Sultan Bello Central Mosque in Kaduna.

-

Interpretation / Implications

-

His deportation from Saudi Arabia suggests that his international mobility, at least in religious-scholar capacity, may be constrained because of political or ideological concerns (according to him).

-

Being back in Nigeria, his influence likely remains strong locally, especially in Kaduna, where he continues his religious work.

-

His mention of “health and farming activities” could indicate a partial stepping back from the more controversial international / mediation roles — at least publicly — though he frames this as a choice rather than a forced exit.

- Questions and Answers

- Opinion

- Motivational and Inspiring Story

- Technology

- Live and Let live

- Focus

- Geopolitics

- Military-Arms/Equipment

- Beveiliging

- Economy

- Beasts of Nations

- Machine Tools-The “Mother Industry”

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film/Movie

- Fitness

- Food

- Spellen

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Other

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Health and Wellness

- News

- Culture