ANXIETY-

Dealing with Extreme Uncertainty.

How irrational thinking can serve you.

Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

KEY POINTS-

Under extreme uncertainty, rational decisions or shortcuts in thinking do not work since information is scarce and people get stuck.

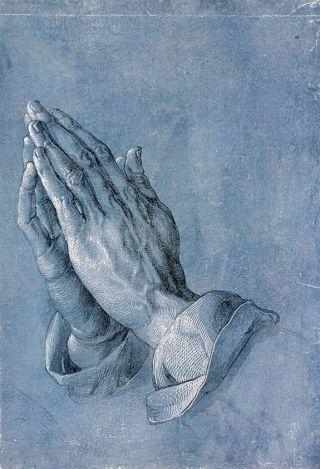

When rational thinking fails, people can turn to eristic (self-serving, wishful or superstitious) reasoning.

Eristic reasoning is self-serving, and it motivates people to keep going.

When uncertain, we typically react initially by seeking the information we need to reduce that uncertainty. We try to find mental shortcuts that help problem-solving and increase the probability of success. This is called heuristic reasoning, and it makes sense when there is enough information to draw conclusions. However, heuristics fail when there is extreme uncertainty because the information is so scarce that any heuristic would be inaccurate.

So, what can you do under these circumstances? In February 2023, a group of researchers suggested that the solution is a type of reasoning called eristic reasoning1.

What is eristic reasoning?

Whereas in heuristic decision-making, decisions are made to satisfy desires by intelligently processing the cues in the external environment (e.g., when stuck in traffic, you may decide to take an exit to find a shorter cut even if you don’t know the way), in eristic decision-making, decisions are made by blindly following desires through self-serving illusory beliefs. Eristic reasoning gives you pleasure and may involve superstitious or wishful thinking.

How can illusory beliefs help?

As a temporizing measure under conditions of extreme uncertainty, eristic reasoning can help. It gives you a sense of purpose. For example, you develop a winning mindset regardless of the circumstances under which you are competing. In some cases, this may work since such beliefs can artificially decrease the anxiety caused by uncertainty, which can boost your performance. The pleasure offsets the discomfort of the uncertainty.

What are the types of pleasure derived from eristic reasoning?

Different types of people will concoct different scenarios for themselves based on their basic needs. For example, a neurotic person may derive pleasure from relieving their anxiety. In contrast, a pleasure-seeking person might seek to bond with others or be sensation-seeking just to keep going. That’s why, when facts are questionable, people turn to their own personalities to satisfy their needs.

How does eristic reasoning show up in our daily lives?

Eristic reasoning is initiated by myths, passions, prejudices and vested interests2. You’ll often see this in political debates, where rather than a weighed argument, the goal is to win the debate at all costs. Sometimes, you see this in legal arguments, where lawyers represent their clients to win a case. One also sees this in the multitude of health-related recommendations that come from experts, where, due to the ample contradictions in the medical literature, people will take one side or another on eating meat, drinking alcohol, exercising a certain way, or following a certain diet. These recommendations are rarely heuristic, even when they are framed that way. They are often self-serving, and the person offering the advice is vested in your following it. You may even follow them to get the pleasure of that bonding and relieve yourself from the anxiety that comes with this.

What are the biases of eristic reasoning?

The biases of eristic reasoning include the overconfidence bias, the endowment effect, status quo bias, loss aversion, and wishful thinking. With overconfidence, the person’s passion is so great that they lose sight of arguments that contradict their own views. With the endowment effect, people often value what they have more highly than if they did not have them. You might, for example, value having a pet after you get one more than prior. Status quo bias keeps people stuck in their own points of view without any propensity to change. Loss aversion makes people attached to their own possessions (even if they don’t particularly want or need them.) And wishful thinking is simply about hoping that something unlikely will happen. One key shift underlying these biases is switching attention away from outside cues to only what will please us.

Why not just rely on reason?

If information sources are not available or reliable, there is no way to reason. This could paralyze you under conditions of extreme uncertainty. Turning to what pleases you is a way to escape that rut. It helps you keep an open mind, though looking for environmental cues is important. The stock market, capital raising, socio-economic shifts, and market dynamics are all situations that can create this kind of extreme uncertainty. Entrepreneurs deal with this all the time. To deal with this stress, eristic reasoning can be very helpful, but it will be dangerous if it consumes you.

Conclusion

Under conditions of extreme uncertainty, you may feel empty, lost, or paralyzed. But eristic reasoning is a way of temporarily escaping these mental states, helping you get to a place where facts will reveal themselves if you are open to them. Satisfying a basic need safely is a good way to get started.

Dealing with Extreme Uncertainty.

How irrational thinking can serve you.

Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

KEY POINTS-

Under extreme uncertainty, rational decisions or shortcuts in thinking do not work since information is scarce and people get stuck.

When rational thinking fails, people can turn to eristic (self-serving, wishful or superstitious) reasoning.

Eristic reasoning is self-serving, and it motivates people to keep going.

When uncertain, we typically react initially by seeking the information we need to reduce that uncertainty. We try to find mental shortcuts that help problem-solving and increase the probability of success. This is called heuristic reasoning, and it makes sense when there is enough information to draw conclusions. However, heuristics fail when there is extreme uncertainty because the information is so scarce that any heuristic would be inaccurate.

So, what can you do under these circumstances? In February 2023, a group of researchers suggested that the solution is a type of reasoning called eristic reasoning1.

What is eristic reasoning?

Whereas in heuristic decision-making, decisions are made to satisfy desires by intelligently processing the cues in the external environment (e.g., when stuck in traffic, you may decide to take an exit to find a shorter cut even if you don’t know the way), in eristic decision-making, decisions are made by blindly following desires through self-serving illusory beliefs. Eristic reasoning gives you pleasure and may involve superstitious or wishful thinking.

How can illusory beliefs help?

As a temporizing measure under conditions of extreme uncertainty, eristic reasoning can help. It gives you a sense of purpose. For example, you develop a winning mindset regardless of the circumstances under which you are competing. In some cases, this may work since such beliefs can artificially decrease the anxiety caused by uncertainty, which can boost your performance. The pleasure offsets the discomfort of the uncertainty.

What are the types of pleasure derived from eristic reasoning?

Different types of people will concoct different scenarios for themselves based on their basic needs. For example, a neurotic person may derive pleasure from relieving their anxiety. In contrast, a pleasure-seeking person might seek to bond with others or be sensation-seeking just to keep going. That’s why, when facts are questionable, people turn to their own personalities to satisfy their needs.

How does eristic reasoning show up in our daily lives?

Eristic reasoning is initiated by myths, passions, prejudices and vested interests2. You’ll often see this in political debates, where rather than a weighed argument, the goal is to win the debate at all costs. Sometimes, you see this in legal arguments, where lawyers represent their clients to win a case. One also sees this in the multitude of health-related recommendations that come from experts, where, due to the ample contradictions in the medical literature, people will take one side or another on eating meat, drinking alcohol, exercising a certain way, or following a certain diet. These recommendations are rarely heuristic, even when they are framed that way. They are often self-serving, and the person offering the advice is vested in your following it. You may even follow them to get the pleasure of that bonding and relieve yourself from the anxiety that comes with this.

What are the biases of eristic reasoning?

The biases of eristic reasoning include the overconfidence bias, the endowment effect, status quo bias, loss aversion, and wishful thinking. With overconfidence, the person’s passion is so great that they lose sight of arguments that contradict their own views. With the endowment effect, people often value what they have more highly than if they did not have them. You might, for example, value having a pet after you get one more than prior. Status quo bias keeps people stuck in their own points of view without any propensity to change. Loss aversion makes people attached to their own possessions (even if they don’t particularly want or need them.) And wishful thinking is simply about hoping that something unlikely will happen. One key shift underlying these biases is switching attention away from outside cues to only what will please us.

Why not just rely on reason?

If information sources are not available or reliable, there is no way to reason. This could paralyze you under conditions of extreme uncertainty. Turning to what pleases you is a way to escape that rut. It helps you keep an open mind, though looking for environmental cues is important. The stock market, capital raising, socio-economic shifts, and market dynamics are all situations that can create this kind of extreme uncertainty. Entrepreneurs deal with this all the time. To deal with this stress, eristic reasoning can be very helpful, but it will be dangerous if it consumes you.

Conclusion

Under conditions of extreme uncertainty, you may feel empty, lost, or paralyzed. But eristic reasoning is a way of temporarily escaping these mental states, helping you get to a place where facts will reveal themselves if you are open to them. Satisfying a basic need safely is a good way to get started.

ANXIETY-

Dealing with Extreme Uncertainty.

How irrational thinking can serve you.

Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

KEY POINTS-

Under extreme uncertainty, rational decisions or shortcuts in thinking do not work since information is scarce and people get stuck.

When rational thinking fails, people can turn to eristic (self-serving, wishful or superstitious) reasoning.

Eristic reasoning is self-serving, and it motivates people to keep going.

When uncertain, we typically react initially by seeking the information we need to reduce that uncertainty. We try to find mental shortcuts that help problem-solving and increase the probability of success. This is called heuristic reasoning, and it makes sense when there is enough information to draw conclusions. However, heuristics fail when there is extreme uncertainty because the information is so scarce that any heuristic would be inaccurate.

So, what can you do under these circumstances? In February 2023, a group of researchers suggested that the solution is a type of reasoning called eristic reasoning1.

What is eristic reasoning?

Whereas in heuristic decision-making, decisions are made to satisfy desires by intelligently processing the cues in the external environment (e.g., when stuck in traffic, you may decide to take an exit to find a shorter cut even if you don’t know the way), in eristic decision-making, decisions are made by blindly following desires through self-serving illusory beliefs. Eristic reasoning gives you pleasure and may involve superstitious or wishful thinking.

How can illusory beliefs help?

As a temporizing measure under conditions of extreme uncertainty, eristic reasoning can help. It gives you a sense of purpose. For example, you develop a winning mindset regardless of the circumstances under which you are competing. In some cases, this may work since such beliefs can artificially decrease the anxiety caused by uncertainty, which can boost your performance. The pleasure offsets the discomfort of the uncertainty.

What are the types of pleasure derived from eristic reasoning?

Different types of people will concoct different scenarios for themselves based on their basic needs. For example, a neurotic person may derive pleasure from relieving their anxiety. In contrast, a pleasure-seeking person might seek to bond with others or be sensation-seeking just to keep going. That’s why, when facts are questionable, people turn to their own personalities to satisfy their needs.

How does eristic reasoning show up in our daily lives?

Eristic reasoning is initiated by myths, passions, prejudices and vested interests2. You’ll often see this in political debates, where rather than a weighed argument, the goal is to win the debate at all costs. Sometimes, you see this in legal arguments, where lawyers represent their clients to win a case. One also sees this in the multitude of health-related recommendations that come from experts, where, due to the ample contradictions in the medical literature, people will take one side or another on eating meat, drinking alcohol, exercising a certain way, or following a certain diet. These recommendations are rarely heuristic, even when they are framed that way. They are often self-serving, and the person offering the advice is vested in your following it. You may even follow them to get the pleasure of that bonding and relieve yourself from the anxiety that comes with this.

What are the biases of eristic reasoning?

The biases of eristic reasoning include the overconfidence bias, the endowment effect, status quo bias, loss aversion, and wishful thinking. With overconfidence, the person’s passion is so great that they lose sight of arguments that contradict their own views. With the endowment effect, people often value what they have more highly than if they did not have them. You might, for example, value having a pet after you get one more than prior. Status quo bias keeps people stuck in their own points of view without any propensity to change. Loss aversion makes people attached to their own possessions (even if they don’t particularly want or need them.) And wishful thinking is simply about hoping that something unlikely will happen. One key shift underlying these biases is switching attention away from outside cues to only what will please us.

Why not just rely on reason?

If information sources are not available or reliable, there is no way to reason. This could paralyze you under conditions of extreme uncertainty. Turning to what pleases you is a way to escape that rut. It helps you keep an open mind, though looking for environmental cues is important. The stock market, capital raising, socio-economic shifts, and market dynamics are all situations that can create this kind of extreme uncertainty. Entrepreneurs deal with this all the time. To deal with this stress, eristic reasoning can be very helpful, but it will be dangerous if it consumes you.

Conclusion

Under conditions of extreme uncertainty, you may feel empty, lost, or paralyzed. But eristic reasoning is a way of temporarily escaping these mental states, helping you get to a place where facts will reveal themselves if you are open to them. Satisfying a basic need safely is a good way to get started.

0 Yorumlar

0 hisse senetleri

1K Views

0 önizleme